Where Horses Roam Free in the Mountains of Eastern Kentucky

The Appalachian Horse Project is ensuring the region's free-roaming horses are kept safe, healthy and, well, free.

Ever since Marguerite Henry’s novel for young readers, Misty of Chincoteague, was first published in 1947, generations of aspiring horse girls and boys have considered nothing to be more magical than the thought of wild, free-roaming horses. One particular little lady I know (ahem…) begged her parents for years (years!) to take a trip to Assateague Island so she could witness the mottled, chestnut-and-white mares and foals frolicking along the seashell-speckled sands. That now-grown gal still has high hopes that she might make it to the annual “pony penning” day to watch the horses swim the channel between Assateague and Chincoteague Islands. (A girl can dream, right?)

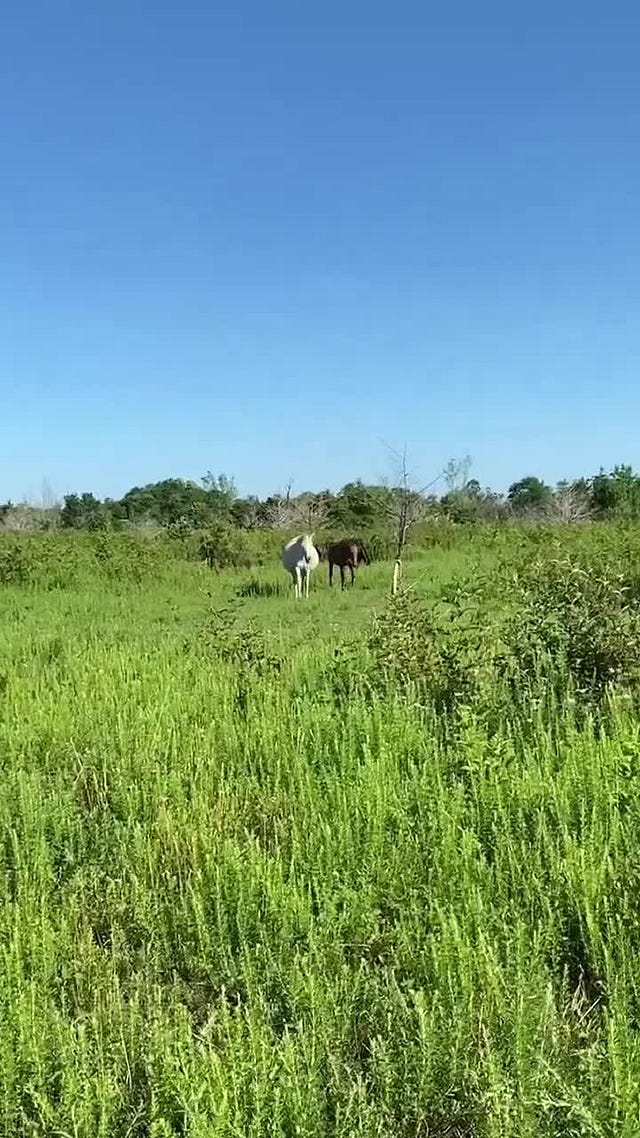

But you don’t have to travel all the way to coastal Virginia to experience the splendor of free-roaming horses these days—you simply have to drive to Breathitt County. For upwards of 30 years, free-roaming horses have grazed along the reclaimed mine lands and newly-flat mountain tops of eastern Kentucky: often to the chagrin of coal companies, but always to the delight of visitors.

The Appalachian Horse Project works to ensure that the largely good-natured, but nevertheless wild, horses that meander along the hillsides of nine counties in southeastern Kentucky are safe, healthy and in the best shape possible to continue their current lifestyle in which equine sovereignty is paramount.

Below, Ginny Grulke, executive director of the Appalachian Horse Project, discusses the overlap between free-roaming horses and coal companies, a city-versus-country difference in what defines “the good life” for horses, and why these mountain mares have such chill temperaments.

Interested in scheduling a tour with the Appalachian Horse Project? Right this way!

(And if you’d like to read more about the history of mountain horses in eastern Kentucky, these oral histories are a great place to start.)

(Photo via Appalachian Horse Project, Facebook)

Sarah Baird: How did the idea for the Appalachian Horse Project come about?

Ginny Grulke: It was almost 10 years ago that the topic came up for the first time. I was executive director of the Kentucky Horse Council, and as part of that role, issues were reported to me relative to horses—all kinds of issues.

This particular situation was one where the coal companies in eastern Kentucky were complaining about these free-roaming horses because the coal companies, before they start mining, have to put a very substantial financial bond down to make sure they reclaim [the mined land] and don't just leave a mess when they're finished mining. Mostly what they do is plant grasses, and so the horses were coming onto the reclaimed land and eating the grass. When those grasses started coming up as little baby shoots, the horses were like, ooh, this is good!…and they kept eating down the grass. As a result, the grass was not growing back to where it needed to be—it wasn’t established enough—and the coal companies couldn't get their bond money back.

They complained to the governor at the time, Steve Beshear, that someone should look into it, and so his wife, Jane, called me and said, “Get a group together. Let's see what we can do about these horses.” So, we put together a committee. That committee met for two years, and nothing much happened except talking: What can we do, what can we do? And then a legislative committee was put together, which I sat on representing the Kentucky Horse Council. They also kept saying, “What can we do? What can we do?”

Nobody knew what to do because there are a lot of these free-roaming horses. With our reputation as the horse capital of the world in Kentucky, the last thing we want to do is make headlines that we rounded these horses up and sent them to slaughter. A lot of them don't have any market value because they’re not registered. I mean, they’re mountain horses—kind of a Heinz 57. You don't know what their breeding is.

Most of the horses at that time belonged to local people, who were letting them up there to graze because they live down in the hollers and there just isn’t much pasture there—it’s all mountainside and wooded. So, they figured, well, here are these thousands of acres that have grass now. Why not put the horses up there?

The practice of letting horses graze like that has actually been going on since the early 1970s, and it normally has worked out well, because there are areas where the grass has totally grown up, and the coal mining companies have been gone for a while and they’ve already gotten their bond money back. And so, everybody was kind of happy.

But when it came to the mined land where coal companies hadn’t been able to get their bond money back yet because of these horses, nobody knew what to do. So, three of us decided to form this nonprofit to make sure these horses were fed and healthy and safe. Also, if the coal company had a group [of horses] on land where they hadn’t gotten bonds back, we would volunteer to round them up and transport them to a place that was already available to horses.

That's how we got started. Our first ambition was to solve the problem with the coal companies, and at the same time, there were horses up there that were too skinny or had an injury. So, we also decided to take care of that.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

SB: How many horses have you helped over the years?

GG: We’ve taken in 75 horses, and we could take in more. I mean, it’s just a matter of where you draw the line on how skinny is too skinny. That’s a lot of the issue. We also pick horses up if they’re in somebody’s private property. For example, if a farmer has a hayfield, and they get in there and start eating down the hay, we pick them up. If they are in the road constantly, we pick them up. If they’re in somebody’s yard, and someone calls and complains, we pick them up. There has to be a citizen complaint before we go pick them up. And then we have to get permission from the animal control officer of that county because we're not a legal, official entity—we’re a nonprofit. But the animal control officers almost always say, “Yeah, go ahead.” It’s less for them to do, and there are enough horses in the area that picking up 75 doesn’t even make much of a dent in the population.

(Photo via Appalachian Horse Project, Facebook)

SB: Could you project how many free-roaming horses there are in Appalachian Kentucky?

GG: We use the number 1,500—and that’s over about nine counties. There are stallions that are breeding the mares every year, so the population keeps increasing. We do also have people illegally taking horses. You’re not supposed to just go up and take a horse, but we do have people doing that. Sometimes horses disappear that we know were up there the prior week.

SB: Is there a county that has a higher population of free-roaming horses than the rest?

GG: Breathitt County has the most, so that’s why we operate out of Breathitt County. They have what we estimate to be about 400 there, depending on how many foals there are.

SB: What’s the relationship like between the Appalachian Horse Project and the owners of these horses? Do they have owners?

GG: When you pick up a horse, they're not micro-chipped or branded or anything, so there's no way to know if they’re owned. We have good relationships with some key people in the horsemen’s group in the area, so if we pick up a horse, we let them know; they spread the word; and we put a picture of the horse on our Facebook page. But we’ve only ever had one horse claimed in almost six years.

Frankly, I think there may be some horses we’ve picked up that did belong to somebody, but what you have to do when you claim a horse is pay all the fees covering what we spent on them. And we always feed them and give them a vet exam and sometimes treat them with medicine if they're not doing well. So, the owner—even if they recognize their horse—doesn’t know what it’s going to cost to get that horse back. We would guess about 30 percent of the horses we encounter are owned by someone.

The other gray area is if you put a mare up there and one of the stallions breeds her and there's a baby, theoretically, the baby belongs to the mare owner. Quite often, though, the owner does not really want the baby, so it’s just left there. There are a lot of those situations, too. When this free roaming thing started, there was a gentleman’s agreement for no stallions up there. It was just geldings and mares. But around 2008—we’re guessing when we had that recession—people started dumping more horses because they couldn't afford them…and they started putting stallions up there. That is really what’s caused a lot of the problems in terms of the population, because they’re just breeding. They keep breeding and breeding and breeding.

SB: Do you think the community-at-large is aware of what’s happening with these free-roaming horses? What's the local response been like?

GG: I would say, in general, the average person that doesn't have horses and lives in the mountains, they either don't care that they're up there because it doesn't bother them…or we have a whole lot of people who have never owned horses who go up and see them and feed them. One couple drives 30 miles one way just to get all the stale bread from the local bakery and take it to the horses. In general, they get good support. I don't think a lot of people quite understand some of the issues, but they enjoy them as an entertainment, you know?

SB: What are the horses like temperament-wise…or does it just depend on the horse?

GG: It depends on the horse and how it has been handled or if it has been handled. In general, these mountain horses have calm temperaments. They’re not high strung. If they’ve been handled at all, they're very easy to work with.

The ones that are three or four-years-old and have never been touched by human hands…they are definitely wild. Even those, though, if you have someone with enough patience, and you put them in an environment where they gets fed and treated well and gets used to humans, they're relatively—I'll say relatively—easy to tame.

(Photo via Appalachian Horse Project, Facebook)

SB: That's fascinating. Why do you think they have such (relatively) chill attitudes?

GG: Their temperament is probably because these mountain horses have always been around this area, and their ancestors were a family horse that took people to church and did plowing. They just were bred to be very easy to handle, and it has carried through. I think that’s the basis of their personality. And then it’s just like people. You have what you inherit as characteristics, and then it comes down to what sort of life you have and how you’re treated, you know?

They’re very approachable, and they’ll eat your food. Now, if you try and put a halter on them, it’s a different story. They’ll run away. If you try and touch them too much or walk around them, they're a little skittish about it. But many of them, especially the babies, they’re just right in your face, like, Hi! The babies are so curious.

SB: How does the Appalachian Horse Project plan to grow over the next few years?

GG: We have a list of things we want to do. First of all, we are giving tours, and we’d like to expand that because we use partial profits from the tours to buy hay and pay the vet bills and that kind of thing.

Eventually, we would like to do equine therapy. There is a lot of need in the area for transitioning from opioid addiction and alcoholism, and there’s no major [equine therapy] program, so we’d like to start that. The other thing we’d like to do if we get a barn is provide some trail riding experiences for novices.

SB: Are there organizations that care for free-roaming horses in other states?

GG: West Virginia also has some of these free-roaming horses, but a rescue association there is actually trying to rid the mountains of them. We would like to keep our free-roaming horses on the mountains but in good condition. So, that’s a big difference.

What we’re doing is still controversial, because if you ask people in Lexington, who are used to thoroughbreds who are really pampered, they’ll say, “Oh, those horses! They just threw them out there, and they’re on their own.” But you wouldn’t believe how happy these horses are! I mean, they just have free rein. They go wherever they want, whenever they want. It’s actually a good life as long as there’s enough to eat. People say, “Oh, they stay out all winter.” And it’s like, yeah, they grow coats. They’re animals. It’s not a problem.

But it’s still controversial. The state veterinarian when we started, who is now retired, said, “We’ve got to get all of those horses off the mountains. They’ll bring in disease, and they’ll impact our thoroughbred population.”

Well, first, the mountain horses are super healthy. I mean, other than food and injury, there’s very little—almost no—disease up there. Plus, they’re pretty much contained and isolated from other herds of horses…certainly thoroughbreds. I think it’s just the idea. People who are used to keeping their horses in barns and pastures can’t understand or can’t relate to letting a horse be out in the wild, you know?

(Photo via Appalachian Horse Project, Facebook)