Tracing a Visual History of Kentucky's Rural Queerness, Part 2

The Faulkner Morgan Archive is preserving LGBTQ+ Kentucky's rich legacy one piece of ephemera at a time.

Today on The Goldenrod, we’re continuing to build a through line of LGBTQ stories from Kentucky over the past 150 years while taking a closer look at the state’s rural queer history and its wide-spread intersections. Using ephemera, artifacts and personal effects from the the Faulkner Morgan Archive—an almost completely one-of-a-kind collection that preserves and promotes the lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer history of Kentucky—Dr. Jonathan Coleman, the archive’s executive director, walks us through his illuminating selections.

If you missed the first half of this piece on Tuesday, start here.

1960s: Lige Clarke

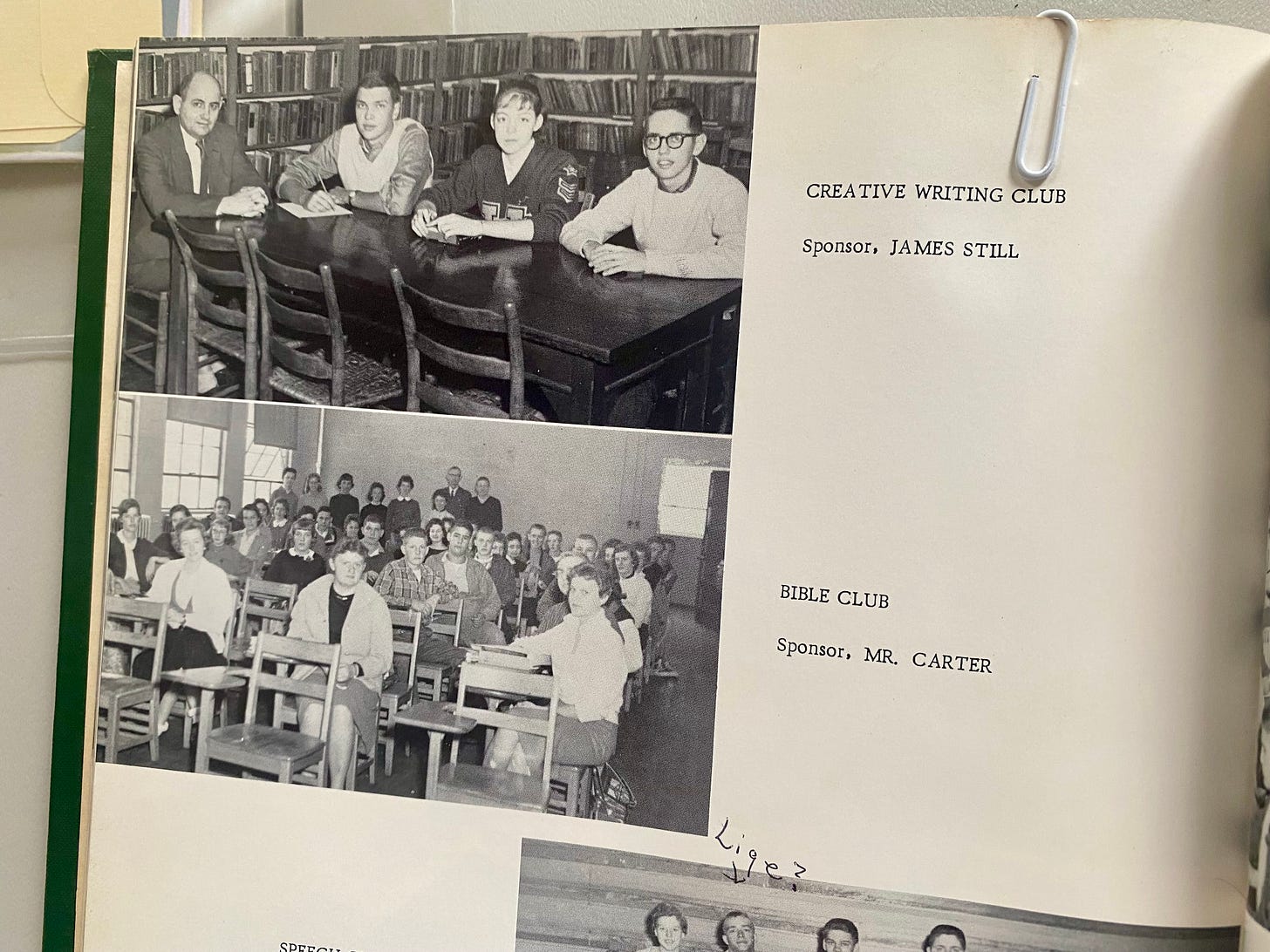

(Hindman High School Yearbook, 1960)

This is Elijah “Lige” Clarke’s 1960 yearbook. You can see his sister, when she handed this to me, put in little notes and paper clips. He’s from Hindman, Kentucky, and the Clarkes were a prominent family in Hindman. It was Lige's great-grandfather, I believe, who brought in the women who did the settlement school. His grandfather has a historic marker on Main Street. Lige was very good looking. There's a picture in here of Lige acting. Lige was in the writing club with James Still.

Lige will go on to become involved with the Mattachine Society, one of the first LGBTQ rights organizations, and in the late 1960s, start the first weekly gay newspaper called Gay. And that’s actually Lige on the cover of the first edition. He and his partner, Jack Nichols, are immensely involved in all of the New York gay stuff. He knew everybody. Lige actually wrote the first published article about what we now call The Stonewall Riots. And he will talk about his hillbilly-ness, his Kentucky-ness, all the time in his work. In fact, Jack, his partner, writes this little bio of Lige, and it’s called “Old Kentucky Homo.”

(Elijah “Lige” Clarke in the Hindman High School Yearbook, 1960)

He was so progressive for his era. Even to the point where he gets in a lot of trouble with the other gay rights activists. Because he rejects a gay identity. At one point he was interviewed by a very famous lesbian couple—the interview is in the New York Public Library now—and they ask him what his sexual preference is. And he says, “My sexual preference is for Jack Nichols.” So he's rejecting essentialism when it comes to sexuality. And he's also rejecting an urbanism.

He makes this argument in one of the essays he writes called “The Great Fucking Famine.” And he basically says, “When I was growing up, I had tons of sexual freedom. No one really categorized anything.” He had sex with both men and women and it was great. And so he thought when he got to New York it’d be better. But there were all these, like, stipulations and understandings about sex when sex can just be for pleasure. He wants a sexual revolution that looks more like Hindman, Kentucky as opposed to New York City. It's a very, very interesting argument to be making in the early 1970s.

(Lige Clarke on the cover of the first-ever edition of Gay)

New York Public Library had a huge 50th anniversary of Stonewall exhibit, and right in the middle of it is Lige Clarke. It's like, “Oh wow, look at what the gays in New York are doing!” But it’s also like, yeah, he is a gay in New York, but he’s actually a Kentuckian. Here’s someone from Hindman right at the center of it. So that urban-versus-rural narrative quickly falls apart.

1960s: C.D. Collins

This is one of my favorite little things. This is C.D. Collins, an author and poet, who now lives in Boston but originally is from Mount Sterling, Kentucky. This is her fake ID from her freshman year of college at Morehead and she entered, I believe, in the fall of 1969. She used this to get into the gay bar in Lexington. She actually started, at Morehead, a group called The Action Squad: all girls, all queer. They were informal, although they did have one meeting with an actual agenda and that sort of stuff. Basically, it was an assumed—although unspoken—series of couples. There in the dorm at Morehead, it was the understanding that someone would be on watch to make sure no one else was around while they were meeting.

I love how here you have this very proud little dyke going to Morehead in the sixties when, of course, Morehead is now so closely associated with Kim Davis as the county clerk. C.D. is still very active and still has a house in Mount Sterling. She spent a lot of the pandemic here and has written quite a bit, including this book here, Blue Land, which is fiction, but very much based in her experiences as a queer person growing up in Mount Sterling. She’s a real joy. Very much a power lesbian.

1970s: Gay Rights Cha Cha at the University of Kentucky

In the early 1970s you have Peter Taylor, who is from Whitley County, and he’s in charge of the Gay Liberation Front at the University of Kentucky, which is a group that tries to get official student recognition. The university refuses to do it. So Peter Taylor, as the president, lists himself as the plaintiff and he sues the university. This starts in 1971, and as this is going on, they make these little newsletters. There are about four or five different ones that are known to exist. It’s all about various things. And they’re very handy because it’s a blow-by-blow of how the case is actually going, including a timeline of when this group first started.

And then they lose their case. [Otis] Singletary was the president at the time, and he famously said that he would ban all organizations instead of recognizing a gay one—even if they did win. The Gay Liberation Front is never acknowledged by the university. But they do get to hold the first openly gay event. That was the Gay Rocks Cha Cha, and Peter made the poster. So here you have this big gay rights event going on in Lexington, and it’s actually led by someone from Whitley County.

1970s: Stephen Varble

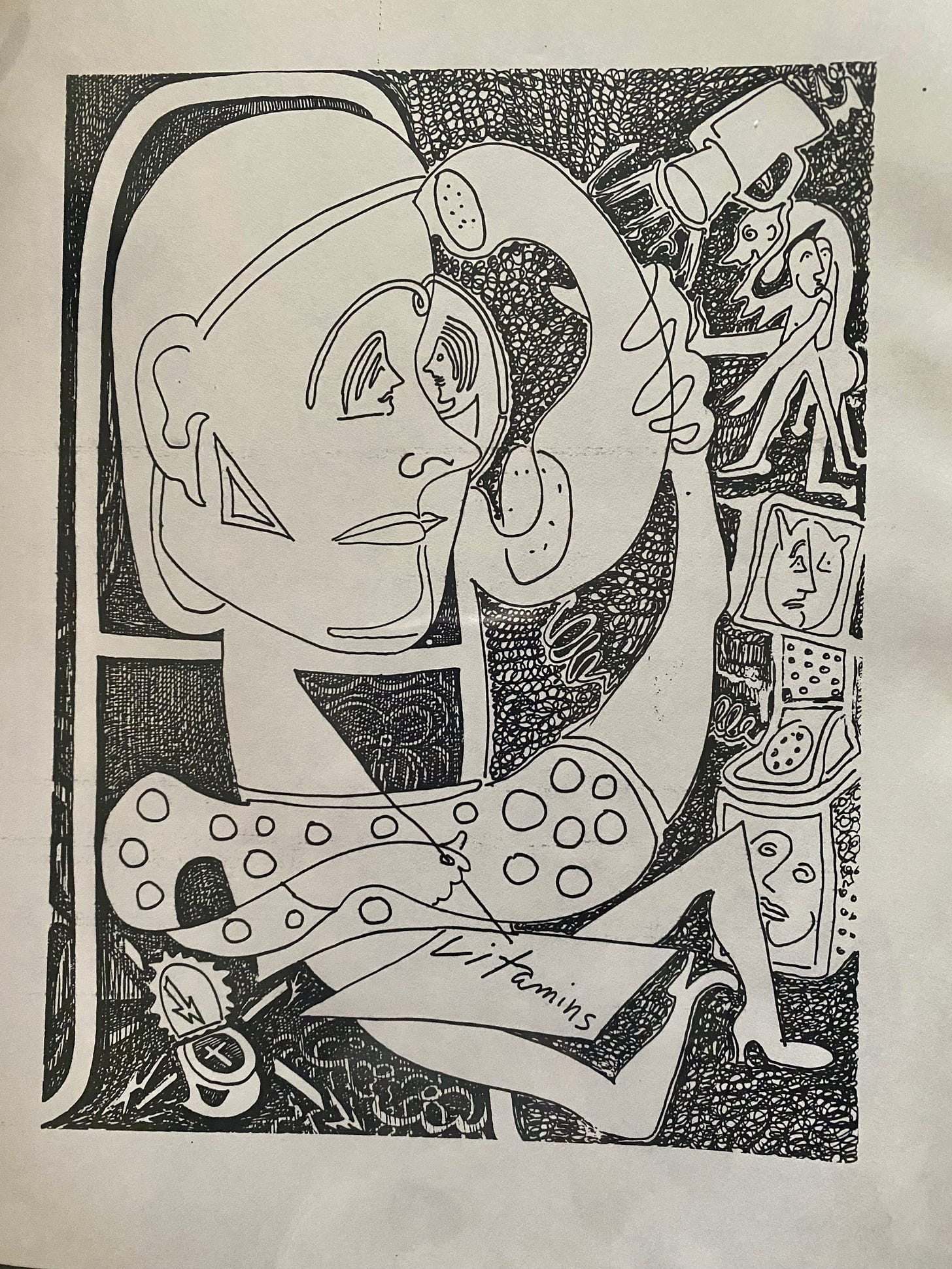

Stephen Varble was originally from Owensboro, and there’s been a big revival of his work recently. He went to UK, and then ended up in New York. There’s an art historian named David Getsy who is writing a ton on Stephen Varble right now, and has done a huge exhibit that has toured in New York and Berlin and all kinds of places. A few of our pieces have been in that show.

Varble intentionally criticized a lot of components of how art is sold and the capitalism involved with producing art, so he intentionally tried to diminish that. He dies early on in the [AIDS] epidemic, his partner dies, and all of his stuff gets thrown out. And luckily someone was walking by his apartment and saved it. So he made these drawings [Ed. note: pictured above] and then intentionally reproduced them as part of the project. I think there are maybe three sets that have survived. Almost none of his other work has survived at all. He was mostly a performance artist, and so it’s really the work of other artists, especially Peter Hujar, that show us the stuff Stephen Varble was doing.

He did some film, that sort of thing. He goes in and very famously protests the bank and has these huge inflated balloons that look like breasts and are filled with cow blood, then he pops them in the middle of the bank. But what's interesting is that you have someone from Kentucky who goes and just fucks up the New York art scene. They really do not know what to do with Stephen Varble.

2010s

This piece is by an artist also originally from Owensboro named Paul Michael Brown—a young man, younger than I am—that he completed a few years ago and then later gave to the archive. It uses very thin, fragile fabrics that tear easily and was designed to get a little torn up with use. It’s meant to carry artifacts and marks from the people that have been in and on it, fucking, talking, doing whatever, most of whom have been queer men. The full quilt text reads: fags, fuck, fear. The words are intentionally obscured so the piece wouldn’t be out of place in a normal home. It’s discernible as a queer object only by someone who happens upon it or has been told. And so Paul basically lived with it for a year.

It is meant to have that hominess, and Paul, of course, made the quilt himself. A very rural identified—a very Kentucky—craft. The International Quilt Museum is here. But he, of course, has turned it into this queer object of the home.

When I asked Coleman if he thought there was some special reason that LGBTQ Kentuckians seem to often be at the heart of the national conversation, it was clear he’s mulled this over for years:

I think there is a Kentucky-specific culture where Kentuckians think about themselves as Kentuckians, probably more so than people from other states. And there is, I don't know, maybe a greater celebration of contrariness, or an appreciation for it. But queer people, of course, have very complicated relationships with Kentucky, because the story is that queer people leave. It's the state of Kim Davis, but it’s not the state of the couple who challenged Kim Davis. And you see that queerness coming out here in the commonwealth itself, but it’s also very visible when queer people leave. Kentucky is always going to come up.

I think there’s a sort of national fascination when it comes to Kentucky, and Kim Davis is a big example. There were county clerks doing what Kim Davis did all over the place. There was one in Upstate New York. There was one in Texas. Yet they didn't get that sort of media coverage. I think a big chunk of it is when you saw her, when you heard her voice, when you heard where she was from, it simply built an entire narrative that you didn't even have to think about. I'm fascinated by what happened with her in 2015. Not because of an instance of prejudice, because that's going to happen all over the place. What I’m interested in is why did this one become the famous one?

And it happens all the time. When Oprah wanted to do a story about AIDS in small town America, she went to Appalachia—the border of Kentucky and West Virginia. The first time federal hate crime legislation was tried was a case that came out of Kingdom Come State Park in Cumberland. This is a pretty constant occurrence.

We’ll be back tomorrow, as always, with legislative superlatives for paid subscribers only. I’ll also be sharing one additional piece of art from the archive that seems to live outside any timeline and is just jaw-dropping extraordinary. Make sure to sign up to see it!