Tracing a Visual History of Kentucky's Rural Queerness

The Faulkner Morgan Archive is preserving LGBTQ+ Kentucky's rich legacy one piece of ephemera at a time.

“These are photos from the Tri-State Gay Rodeo Association—that’s what they called themselves—and they would ride their horses; they would go to rodeos; they would hold these dances. They were really taking ruralness on as a queer behavior in and of itself.”

Dr. Jonathan Coleman and I are hunched over a weathered photo album from 1991, flipping through 8x10 pictures of men wearing bleached-out tight-fitting jeans two-stepping arm-in-arm and twirling in cowboy boots and Stetsons across a dance floor. “This one was in Lexington, I think. It’s so funny because you hear a little bit nowadays about that whole gay cowboy scene, but you just never see it anymore. I’m sure maybe in some places you do, but not around here.”

The album is such a moment in time for queer culture in Kentucky: an intimate snapshot of what life was like for a certain group, on a certain day, here in a place that most people nationally (or probably locally) wouldn’t associate with a storied, robust LBGTQ history. But the snapshot memory of the Tri-State Gay Rodeo Association is only a fraction of the one-of-a-kind ephemera, artifacts and personal history housed at the Faulkner Morgan Archive.

Cofounded by Coleman and artist Robert Morgan in 2014, the Faulkner Morgan Archive collects, preserves and promotes the lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer history of Kentucky. The collection currently houses 15,000 items and more than 250 hours of recorded interviews—94 percent of which is completely unique.

“We are very selective about what we take in. We have to be. So we only take things that are directly tied to LGBTQ Kentuckians. It can't be widely produced material. If someone came in and wanted to give us a hundred issues of The Advocate, for example, we wouldn't take it. Around 94 percent of the archive is unique. It's the only copy of it that exists.”

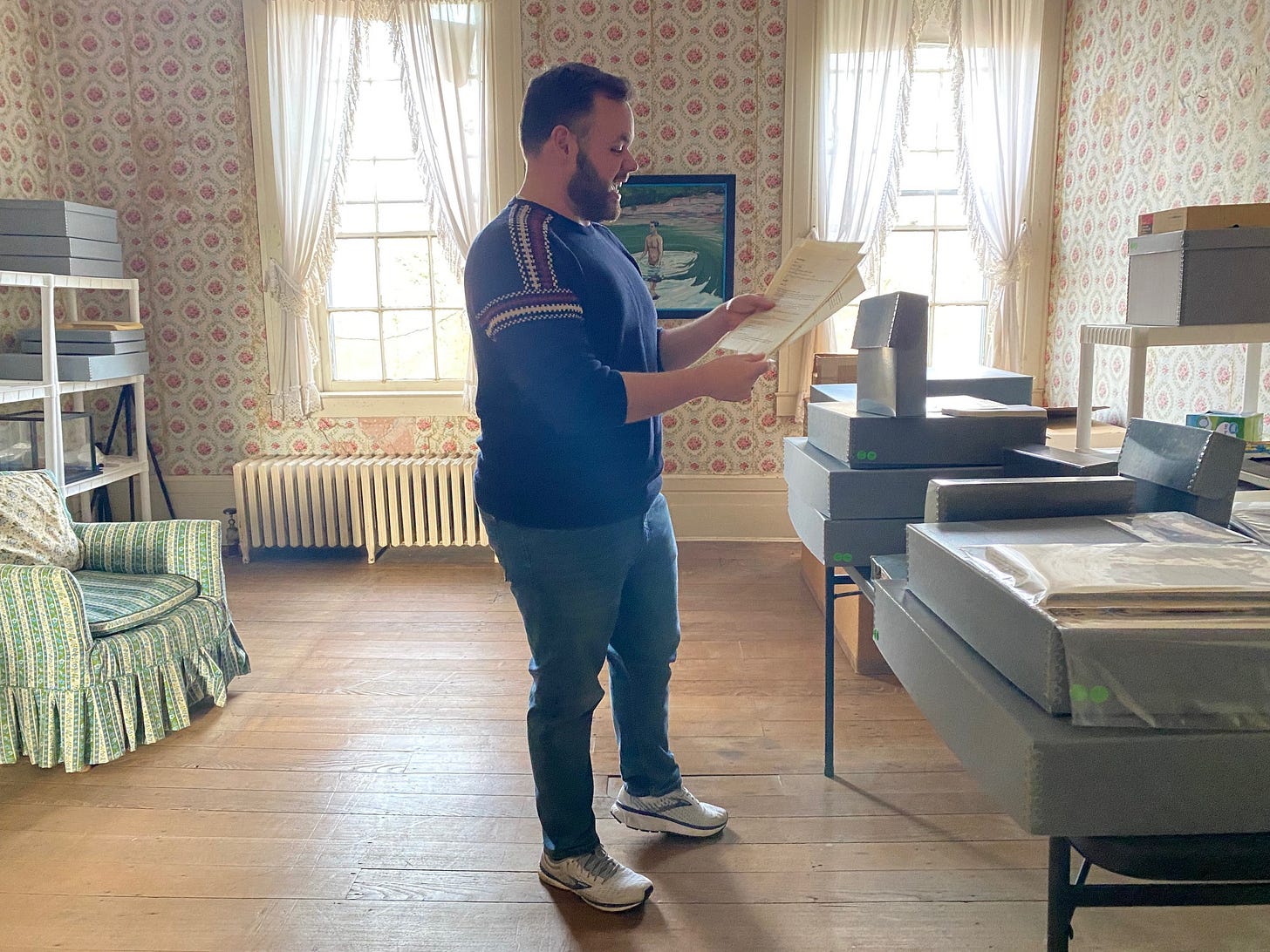

(Coleman reviewing documents at Faulkner Morgan Archive headquarters)

Started partially because Morgan worried that any museum already in existence wouldn’t know what to do with all the queer erotica in the collection, I approached Coleman about how we could use the artifacts in the archive to build a sort of LGBTQ timeline for rural Kentucky: What do the archives tell us about what was happening 100 years ago? 50 years ago? But he quickly expanded my vision.

“When I think about queer rurality or rural lives of queers, those distinctions quickly break down, right? They're as socially constructed as gender and all of that,” Coleman, a Pikeville native, notes. “As someone who does queer history from Kentucky, there is an assumed metro-normative narrative to the gay liberation movement or whatever you want to call it. But those things don't really work out. And that's also true when you shorten the scale, right? You can't talk about queer history and Lexington or Louisville without moving outside of it and vice versa.”

This week, we’ll be exploring a handful of objects pulled by Coleman from the archive, along with his expert explanations, that build a through line of the state’s LGBTQ stories from the past 150 years and reveal a history of Kentucky that’s been largely overlooked for far too long.

Late 1800s

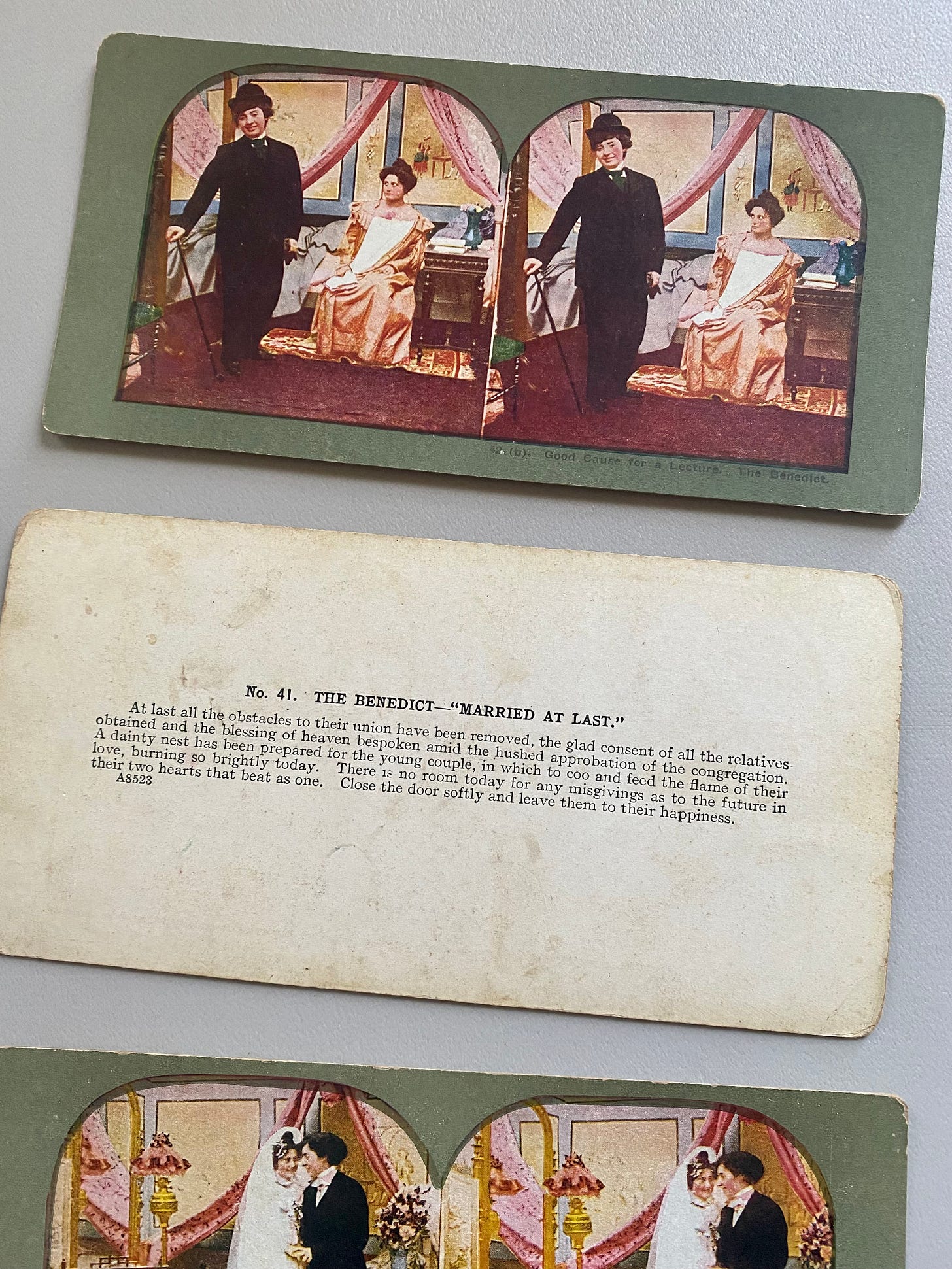

The first item I’ve pulled out are these stereoscopic cards. You know, you put them in the little viewer. [Ed. note: stereoscopic cards contain two nearly identical photographs paired to produce the illusion of a single three-dimensional image when viewed through a stereoscope.] These were found in Georgetown, Kentucky and they date right to the turn of the 20th century or late 1900s. And what's fascinating about them is that we have no idea where they came from. We have no idea who originally owned them. But it's an all-female marriage.

Now these could simply be a parlor joke. But if you're a queer person, if you're someone who sexually desires the same sex, and you saw this, what would this mean to you? What kind of worlds could it open up? And they are very openly playing with desire here. They have a baby. You get to see a full relationship progression. And it's so funny. "I wonder where she got her blue eyes?" It's this sort of joke, right? "He might not be the biological father." Of course this person isn't the biological father! But they're still playing with it.

Early 1900s

There was a gay man from Louisville who was actually sort of a famous celebrity trash collector. And he later retired, came back here, and would go through these antique stores and find photographs of what he called “sissy men” and “butch women”. And the only thing was that they had to be from Kentucky. The photographs had to be in Kentucky. And so they're all anonymous, we have no idea who these people are, and once again, we don't know what their relationships are, but they're all playing with gender.

It helps sort of build a case of what's going on in rural Kentucky. And it's supplemented by scant evidence that made it into things like police reports and newspapers. In fact, when I see these, I'm always reminded of an article that appeared in the early 1900s. The newspaper was from a small town in western Kentucky, and all that the title said was, “Mr. Bark was a woman.” And it explains, “Mr. Bark has lived in this community for 13 years. He died last week and on his deathbed confessed that he was a Miss Green.” And that's it, that's all we know. You know, why was Mr. Bark being Mr. Bark? There are these little things that still pop up. So we have this physical evidence, right, of multiplicities of gender, but the specifics are a little less clear.

1930s

It would be hard to not talk about Henry Faulkner. [Ed. note: He’s the “Faulkner” in Morgan Faulkner Archive.] This is a photograph that stayed with Henry until the end of his life. And that is him on some property in Clay County, where he was raised. You can see his: me, age 12. This would've been in the '30s, and here you have this figure who is going to be so notoriously gay, very open about his sexuality and tied to national and international art circles, all of that, and he's having this experience in eastern Kentucky. While he leaves it, he has a complex relationship with Clay County.

He was very famously put up for adoption by his biological father after his biological mother died, so he's sort of a ward of the state. And he does have foster parents in Clay County that he calls his mother and his father, but he also has a sort of state advocate. So she's always keeping track of what he's up to—and he's up to a lot. We know he’s doing drag, we know that he's having sex with men. He gets arrested—I think he's 16—in Louisville. I think he’s in his mid-twenties when he’s arrested and taken to St. Elizabeth's, which is outside of D.C., and put in Howard Hall, which is where they put the criminally insane. There are lots and lots of reams of paper about his sexuality there. So, he's talking about being in Clay County and tells a story about riding a mule with a boy, and then they have a “go off in the woods” kind of thing. We have an immense amount of information about Henry's sex life. He does an interview with Alfred Kinsey. It’s fascinating.

But he never denies the role that Clay County played. And many times he would even exaggerate. Later on: He's a native painter! He's from Egypt, Kentucky! All this sort of stuff. And it plays up this sort of rural savant figure. He'll spend time in New York, of course, and Key West in the winters. But it always ties back to eastern Kentucky.

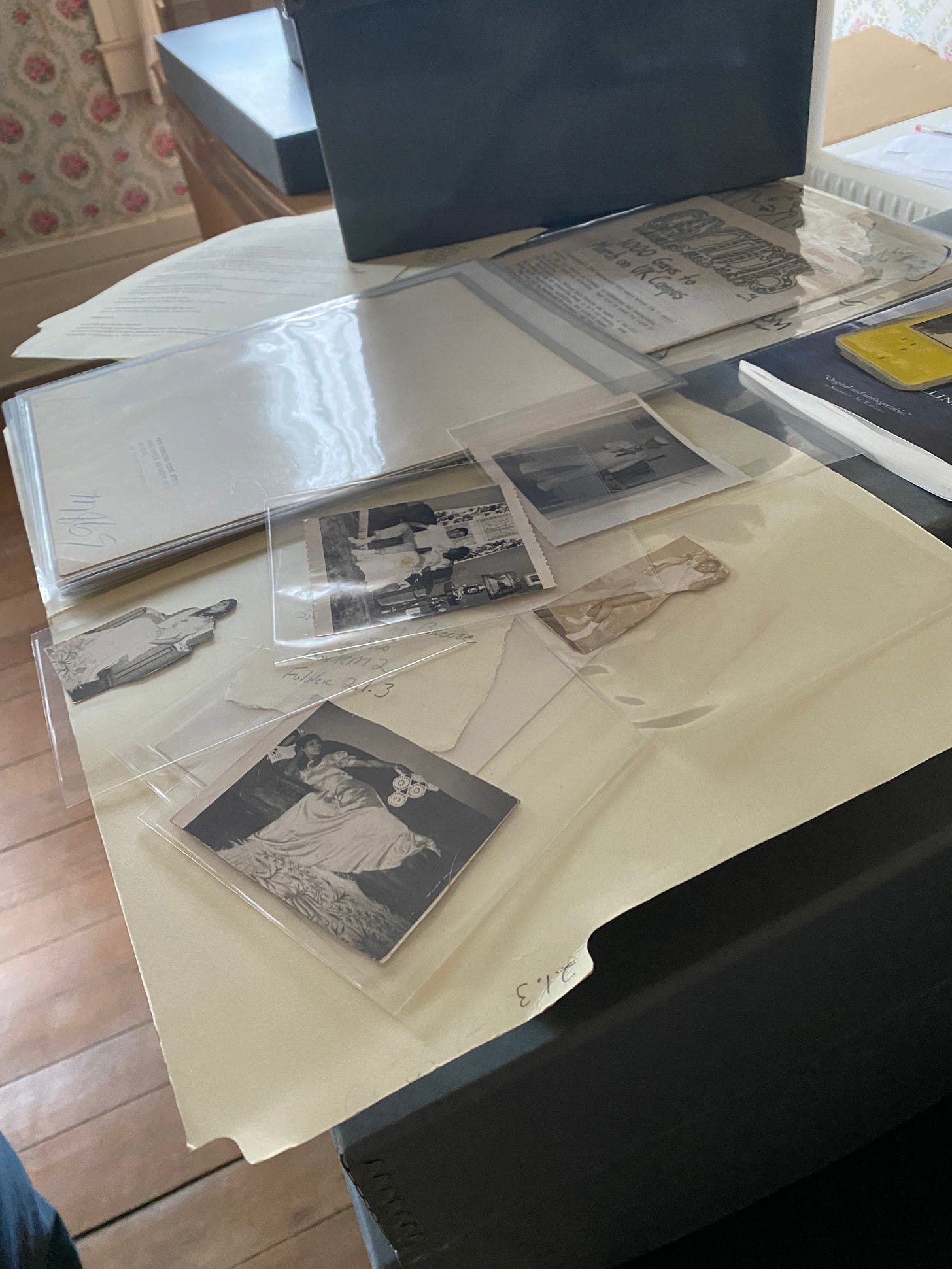

(Archival photos of Sweet Evening Breeze, matriarch of the Lexington drag scene, who is now memorialized in mural form on North Limestone.)

With ruralness, it’s always a challenge, because if you're telling stories through the material that survives, you know you're missing out on so much. There are so many silences here. I have told no Black stories. I've told no super early stories. And how do I do that with the material?

The material exists—I'm sure it does. I know the story does. And so I find it where I can find it. If we weren't looking at artifacts in the archive, if we were looking at documents, it’s easier to do. Because the documents exist. The other actual material from their lives does not. So, how do you do that when you're looking at a historically oppressed, marginalized community that has so many intersections on it like race; like gender; like gender identity; like social class; and, in this case, like location? If they were in Lexington, or Louisville, stuff got saved. If they weren’t, where does that stuff go? It's a constant challenge, and it's such a rich, diverse, important story. How do we tell it as completely as we can?

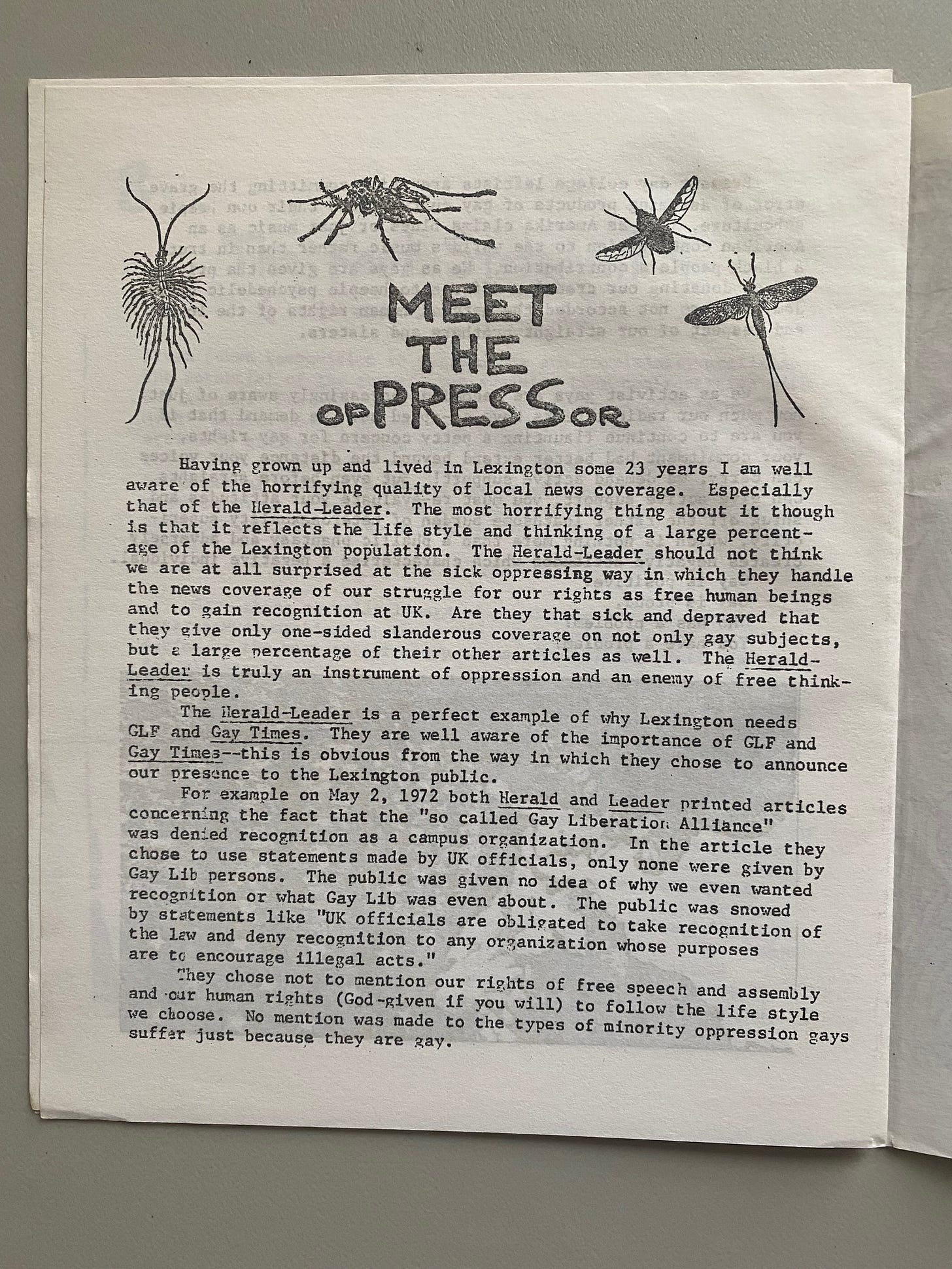

We’ll be back Thursday with the 1960s-through-today portion of this timeline. As a little teaser, though, I wanted to share this essay from one of the ‘zines we’ll be highlighting that, in many ways, pinpoints the work we’re trying to do with The Goldenrod.

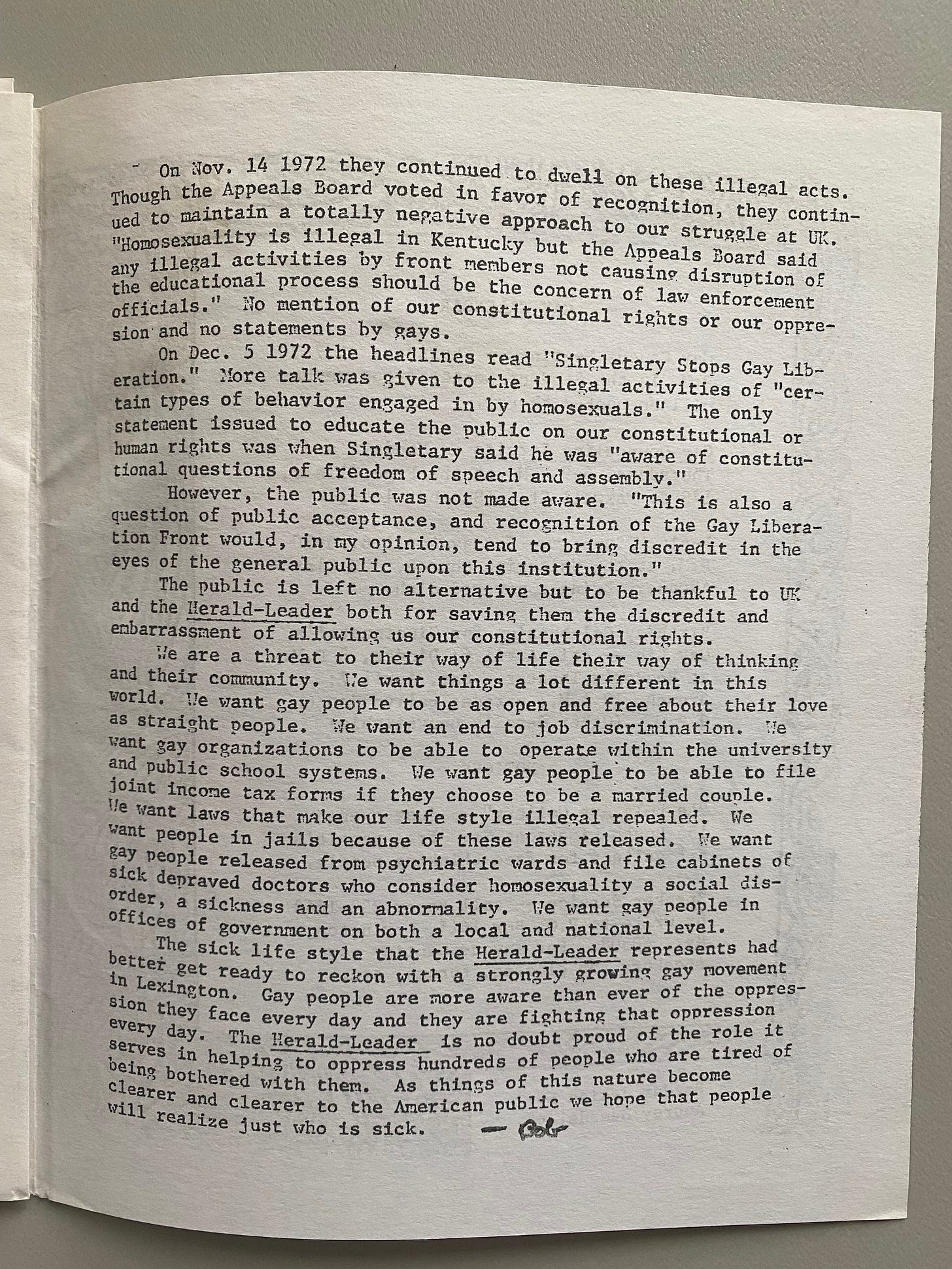

Entitled “Meet the oPRESSor”—with some delicately ominous insects floating around the edges of the page—this scathing takedown of the Lexington Herald-Leader was written in 1972 and tackles, at length, how the newspaper failed to include gay voices in its reporting about the Gay Liberation Alliance’s efforts to be recognized as a student group at the University of Kentucky. (More on that Thursday.) But fifty years ago, in the paper of record, there were zero gay voices in an LGBTQ story. Zero.

The piece is such a strong remind for all lovers of (and advocates for) close-to-home reporting that just because journalism is local, doesn’t mean it’s necessarily good or fair journalism.

“Having grown up and lived in Lexington some 23 years I am well aware of the horrifying quality of local news coverage. Especially that of the Herald-Leader. The Herald-Leader should not think we are at all surprised at the sick oppressing way in which they handle the news coverage of our struggle for our rights as free human beings and to gain recognition at UK,” the essay blisters.

“For example on May 2, 1972 both Herald and Leader printed articles concerning the fact that the ‘so called Gay Liberation Alliance’ was denied recognition as a campus organization. In the article they chose to use statements made by UK officials, only none were given by Gay Lib persons. The public was given no idea of why we even wanted recognition or what Gay Lib was even about. The public was snowed by statements like ‘UK officials are obligated to take recognition of the law and deny recognition to any organization whose purposes are to encourage illegal acts.’

They chose not to mention our rights of free speech and assembly and our human rights (God-given if you will) to follow the life style we choose. No mention was made to the types of minority oppression gays suffer just because they are gay.”

Local journalism has a long history of ignoring or suppressing marginalized voices along the lines of race, sexual orientation, gender, socioeconomic status and beyond, and treating the earlier eras of news like they were the good ‘ol days of providing everyone with information, frankly, isn’t true. It doesn’t take a deep dive into pieces from 70, 50 or 10 years ago (and some would say now!) to see that there isn’t a balance of power when it comes to what voices make it into a story, as newsrooms filled with white cis men often catered to an audience that looks like them.

Over the past five years, in particular, I’ve been on plenty of panels about “news deserts” and all that the term entails—I have enough Save Local News! tote bags that my bags are in bags—but “bringing back” local news has the sort of hollow ring for me as saying we should “return to normal” whenever this pandemic slows to a crawl. Local news needs to be completely reimagined if it’s going to be meaningful. We’re trying to play a small part in that.