Roadside Shrines and Bathtub Madonnas: "Connecting with One's Faith through Artmaking"

Harlan-based photographer William Major is taking a closer look at religious iconography in Eastern Kentucky and beyond.

Religious iconography is woven into the landscape of Central and Eastern Kentucky as dense and thick as Queen Anne’s lace.

From chipped-paint bathtub Madonnas jutting up out of front yards, to the proliferation of cheesy-meets-prayerful church signs with quips like Son Screen Prevents Sin Burn, to plastic-flower-covered spontaneous roadside shrines a la Three Wooden Crosses, it’s a matter of day-to-day expediency that—more often than not—we simply breeze past this imagery that’s so deeply embedded in our drive-by psyches. But much like the thickets of purple dead nettle and pokeweed in the ditches, once you slow down to take a closer look at this public-facing, Jesus-tinged art instead of regarding it as part of our day-to-day set piece, there’s plenty of beauty and deep truth to be found there.

That’s exactly what Harlan-based photographer William Major wants to accomplish with his new collaborative book project, Icon & Spirit.

A Johnson City, Tennessee native, Major has been drawn to religious iconography in all its myriad forms since he began taking pictures as a youth, inspired by his Bible Belt upbringing as well as his grandfather, who often used his skills as a sign painter to illustrate Bible verses. With the Icon & Spirit publication, Major hopes to capture a wide swath of individual experiences with religious totems, images and artwork—and encourages submissions from anyone who would like to share their impressions or interpretations on the themes. (No professional art training required!)

Learn more about the inspiration behind the new project below, and read to the end for an opportunity to win one of Major’s other mini-books, BLM: Rural Resistance in Appalachia, which documents the Black Lives Matter protests across Eastern Kentucky during Summer 2020.

All photos by William Major.

Boone’s Ridge, Bell Co. 2020.

Coldiron, KY. 2020.

Sarah Baird: When did you develop an interest in bookmaking?

William Major: I think anybody who gets into any sort of art meets gatekeepers, in the sense that you have to know the right people or have the right credentials—yada, yada, yada—and I am a firm believer that's a bunch of shit.

The book I made last year is about wrestling. At first, it was just going to be my friend and me publishing this thing together because he has a love for the sport, too, and we have similar artmaking tendencies around wrestling. But we decided that it would be more interesting to have a fuller conversation and have other parties involved. We wanted it to be a collaborative effort, and also give access to people who had never been published before. Just involving a whole gamut of people—even wrestlers.

We framed it all within the guise of people who are fans of the sport making art about it in multiple iterations. We were bridging the gap, essentially, between someone who gets paid to make art all the time, versus someone who just does it maybe as a hobby, versus someone who’s really just passionate about what they do in the ring. We brought all that together and made a book out of that, like old DIY-type ‘zine-making, but into a more slick looking mini-book. I just find collaborations more enjoyable than, “Here's my stuff. Look at it.” I'm not as interested in that.

Middlesboro, KY. 2020.

Dizney, KY. 2020.

SB: First, wrestling book. Second—religious iconography?

WM: Laughs. Yeah, I think that comes from growing up in the Bible Belt with religious communities around me all the time, and just seeing this need for people to create Christian iconography in some way, either on the side of the road, or by their house, or in front of churches.

It also stems from my grandfather being a sign painter. He worked at a paint company, but he also did a lot of painting just for himself. He had this constant need to create something. And a lot of [his work] had to do with either verses from the Bible or something Christian-related—visual representations that he knew and understood. He was making art out of that.

So, when I first started photographing, that's what I gravitated towards was this way of connecting with one's personal faith through artmaking. And that can either be through roadside stuff or going into cemeteries and seeing how people dress their family's graves. It’s always fascinated me. I think it's a facet of Appalachian culture that is indicative of the place and the people. And since I've been in Harlan, it's been more amplified. I’m seeing a lot more of that.

Bell County, Kentucky. 2020.

Totz, KY. 2020.

SB: Do you think religious artmaking in Appalachia is more performative or personal? Or is it a mix depending on what you see?

WM: Oh gosh! I don’t know. I think I just started photographing this stuff at a young age, and it's almost like keeping a catalog or seeing a topographic repetition happening around you. You sequence that out to try and make sense of it for yourself, but also to make sense of the space you live in and are from. It's like I'm an outsider, but I'm an insider at the same time, when it comes to that type of representation.

SB: What kind of imagery is taking shape for the book so far?

WM: It's still very much in the rough draft period, but a lot of the work right now is roadside stuff: artists that do similar things that I do with photography. I'm also talking with some painters who do religious-type painting. One person I'm talking to actually is in prison, for a murder, but he became a monk and a Christian while in prison. He does all these kinds of Eastern Orthodox icon paintings, and he and his brother—who’s a tattoo artist—collaborate with each other and it's fascinating. And then there's another person I've been talking to who grew up in Branson, Missouri, and they are photographing on a very quiet, almost poetic level, the spectacle of biblical tourism that happens in Branson. It's interesting that there are these places in America we’ve created as these weird capitalistic holy lands.

I'm definitely centering [the book] in Appalachia, but I also want to get this worldwide lens reflecting what religious iconography means to people across the world.

Harlan, KY. 2020.

SB: Do you think religious iconography has taken on a new meaning in the wake of COVID, with so much death and polarization?

WM: I’ve got to stew on that a little bit, but yes. I think more people are being faced with their own mortality and figuring out: What are my beliefs? Who do I believe in? What do I believe in?

I think when the whole world is experiencing COVID and also extreme climate change, that definitely does wake up a lot of either good things or bad things in people. It could be trusting in oneself, maybe, and trusting in the people around you. Or it could be trusting in false prophets, trusting in false politicians, false police. The foundation that we thought was somewhat sturdy is sliding, and people are trying to hold onto whatever feels solid or can give them a sense of comfort.

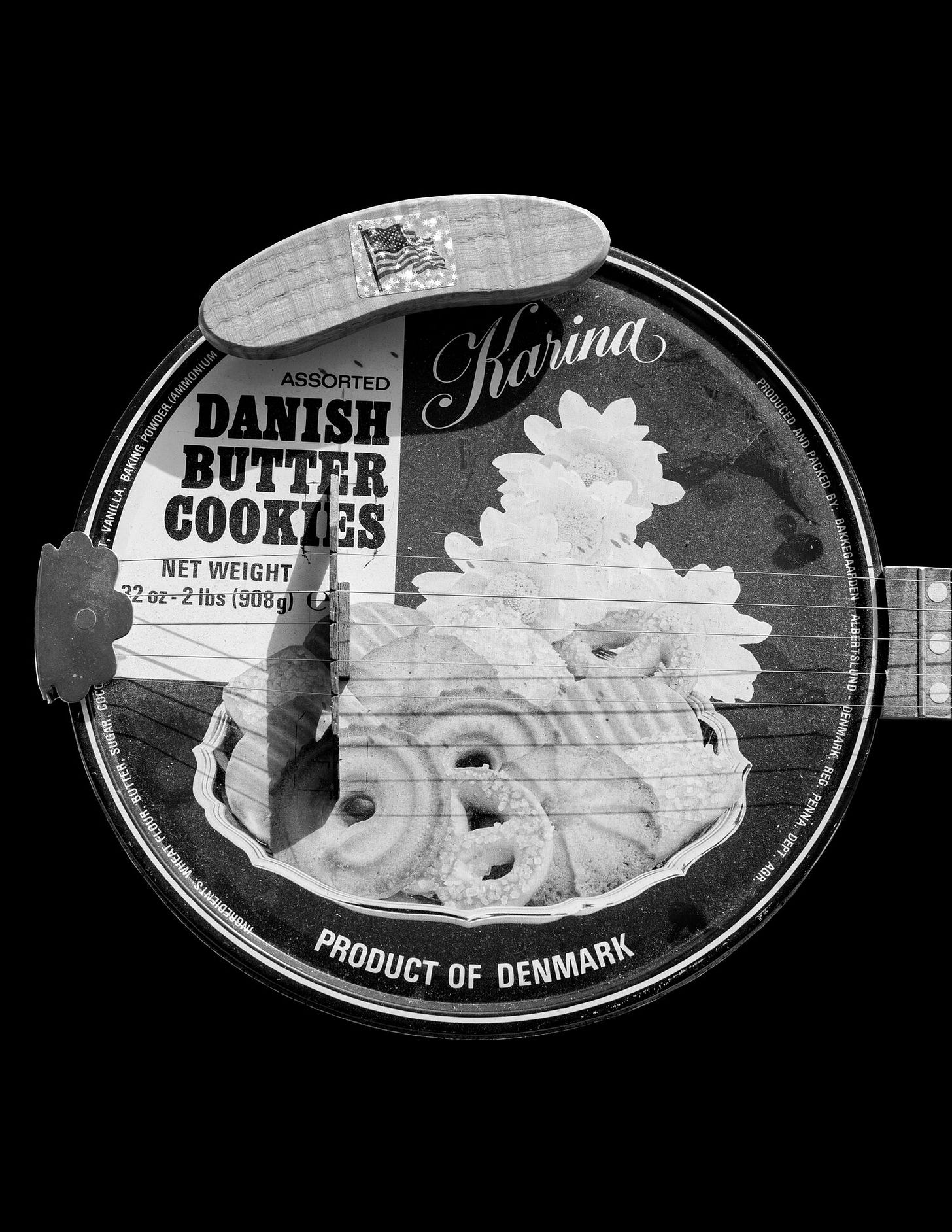

Al Cornett, master luthier, Cumberland, KY. 2020.

Al’s Banjo, Cumberland, KY. 2020.

*Radio announcer voice* And here are those giveaway details!

Subscribe to The Goldenrod—if you haven’t already—then leave a comment below with the best way to get in touch (social media handle, e-mail, whatnot) and describe a time you’ve had what you consider to be a “religious” experience. It can be sacred (like singing “How Great Thou Art” as a duet with your mamaw) or secular (like your first bite of a fresh plum) but must be uniquely your own. Don’t fib, y’all!

Four winners will be selected at random on September 9 and notified through their preferred contact method within 24 hours. We’ll share some of the comments as part of an upcoming newsletter, in case you’re interested in what your neighbors and newsletter compatriots consider to be a religious experience. (I mean, who isn’t?)

And if you know someone who would love to win one of Will Major’s BLM: Rural Resistance in Appalachia mini-book, why don’t you share this story with them?