Home Heating Oil Prices Are Skyrocketing in Kentucky

Costs have reached record highs—and many rural households are struggling.

Whether you’ve stared in disbelief as the dollar amount ticked higher and higher at the gas pump or experienced sticker shock in the grocery aisle over everything from orange juice to bacon (up .25 cents and $1.18, respectively, year-over-year, since 2021), there’s no denying that prices are rising, with no signs of slowing, when it comes to day-to-day necessities for rural Kentuckians. Everyone is talking about it, and it seems like everyone is concerned (except, say, elected officials)—from the cousin who is running on fumes to work, to the neighbor who can’t seem to find formula anywhere—but it’s difficult to see any viable avenues for relief. Instead, it’s the sort of squeezing, slow-creep hardship that feels like death by 1,000 tiny cost upticks.

One less prominently discussed, but critical, issue deeply impacting many rural Kentuckians is the soaring cost of home heating oil and kerosene. A method of warming houses that can work in remote areas outside the traditional electrical grid and with mobile or manufactured homes*, oil heating systems are a staple across the mountains of Appalachian Kentucky and other just-out-of-town places around the commonwealth. Their exact distribution and prevalence, however, isn’t tracked by any state metric, meaning that thousands of Kentuckians, or more, might be silently carrying a financial burden with limited ways to access help.

But first, a little bit more about home heating oil. (We’ll circle back on kerosene—specifically kerosene heaters—and their unique issues in a moment.) Home heating oil and kerosene are both products of crude oil processing, meaning that their price is tied to the commodities market and, yes, political climate. Despite falling largely out of favor in more populated areas of the state, it works well for many rural reaches because it heats up faster than gas and isn’t susceptible to power outages like electric. It will go where other energy sources (except, of course, solar) can’t or won’t.

Technically speaking, if a heating tank is inside the home, heating oil is typically used. If your tank is built on the outside of the home (like with many mobile homes), heating oil or a kerosene-and-heating-oil blend should be utilized to maximize effectiveness when temperatures are well below freezing. According to the 2019 Kentucky Energy Profile, Kentucky consumed 33,000 barrels of home heating oil in 2017, with the residential sector “by far the largest consumer…[with] 47 percent of the total [used] for home heating” amounting to $1.5 million in expenditures. In 2019, Kentucky was the 27th largest consumer of home heating oil in the nation according to U.S. Census data. (New England pretty much rounds out the top ten for obviously blizzard-related reasons.)

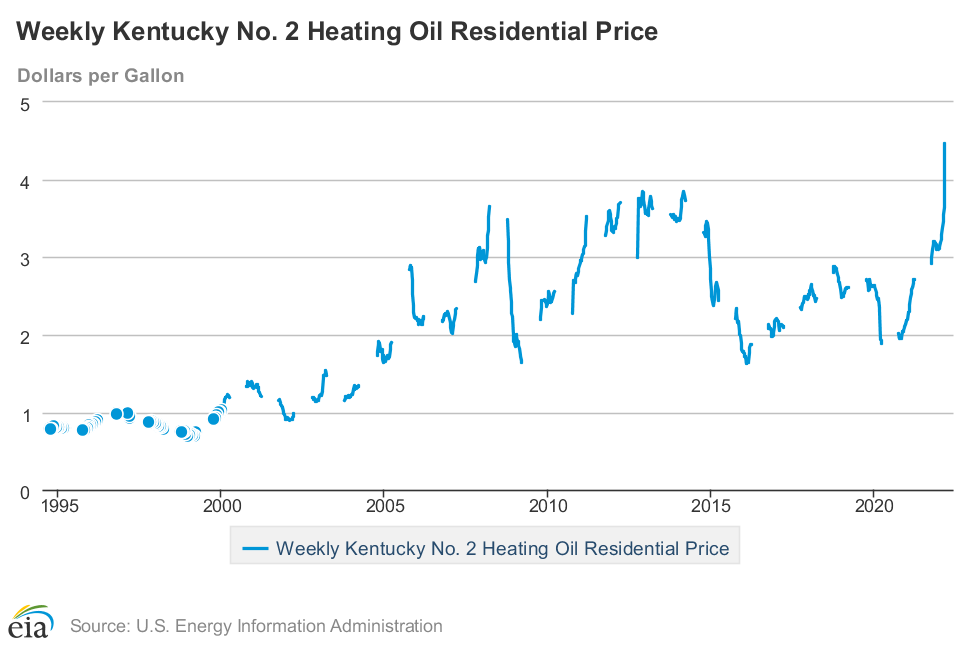

Now to the troubling part. Home heating oil prices are the highest they’ve ever been in Kentucky since the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) started tracking the numbers way back in October 1994, currently clocking in at a whopping 4.47 dollars/gallon. That’s almost two dollars more than March 2021, and .62 cents higher than the previous record of 3.84 dollars/gallon set in February 2014. (I truly can’t recall what was happening in 2014 to cause prices to spike like that, but if you have a wager, please chime in down below in the comments.)

But how many Kentuckians on a household-by-household basis this is impacting can’t really be unearthed. There’s no county-by-county tracking for who uses home heating oil versus other methods in Kentucky, according to the state Energy and Environment Cabinet, though by using federal data via the American Community Survey (ACS) from 2019 and 2012 (the results from 2020 and beyond have been delayed until later this month) it can give us a small peek into some potential rural-versus-urban distribution and, in turn, room for comparison.

The 2019 version of the survey reports that approximately 9,447 Kentuckians use heating oil or kerosene as a primary residential heating source, but the survey doesn’t delve into any county-by-county breakdown outside of Jefferson. (Bummer.) The 2012 version of the ACS actually does breakdown several larger Kentucky counties, and while the data is very limited, it’s enlightening. Pike County (pop. 25,716), for instance, had roughly 102 households using heating oil as a primary residential source, while Fayette County—which had, in 2012, almost five times the total number of households—only had 91 homes using heating oil or kerosene as a primary source. It’s not hard to extrapolate that using home heating oil is a largely (perhaps almost exclusively) rural Kentucky issue, and with the current price spike, people in our hills and hollers are hurting.

When I reached out to Community Action Kentucky, the organization responsible for administering services through the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) in the state, opportunity lead Katlyn Miller reported that even they “do not track feedback provided by people who receive LIHEAP services.” This surprised me, then seemed a little more troubling: there appears to be no organization out there tracking who is reliant on currently ultra-expensive heating oil to warm their homes—even those tasked with assisting families with demonstrated need.

And then there’s the issue of indoor kerosene heaters. These sources of “secondary” heat are widespread for those in Appalachian Kentucky who frequently experiences power outages, whether from extreme weather events (like, ahem, a huge March snowstorm) or the kind of glitches in shaky electrical grids that seem to happen all-too-often. Health and environmental worries aside regarding the heaters (though, please, if you use them, do so safely!) even relatively small quantities of kerosene have become increasingly scarce and difficult to access over the past few months, with message boards and mutual aid groups constantly filled with worried Kentuckians asking where to buy—or how to afford—kerosene for their heaters. When I inquired about it on a recent trip to Tractor Supply in Clark County, the store clerk looked at me, befuddled. “We haven’t had any kerosene for sale in months,” she said, shaking her head like I had asked a truly foolish question.

(Wherefore art thou, kerosene?)

In times of record-setting home heating oil prices, it calls to light a significant local government oversight that we simply don’t know how many Kentucky households—particularly those in rural Kentucky—are warming their homes. Electric companies keep month-to-month (er, day-to-day) records of who is using their services because they’re profiting off of it, but it should be a government responsibility to have a better general idea about how all citizens are heating their homes so that help can be more readily administered in times of need. This isn’t just an issue with data collection: it’s a matter of safety, well-being and community support.

*The term “mobile home” technically refers to any factory-built house constructed before the HUD Act of 1976. If it was built after 1976, it’s called a manufactured home. A personal hill I will die on!