Heaven Hill’s “Striketober” Was Nothing New for Kentucky Bourbon

The state's signature spirit has a long history of public-facing growth and behind-the-scenes labor struggles.

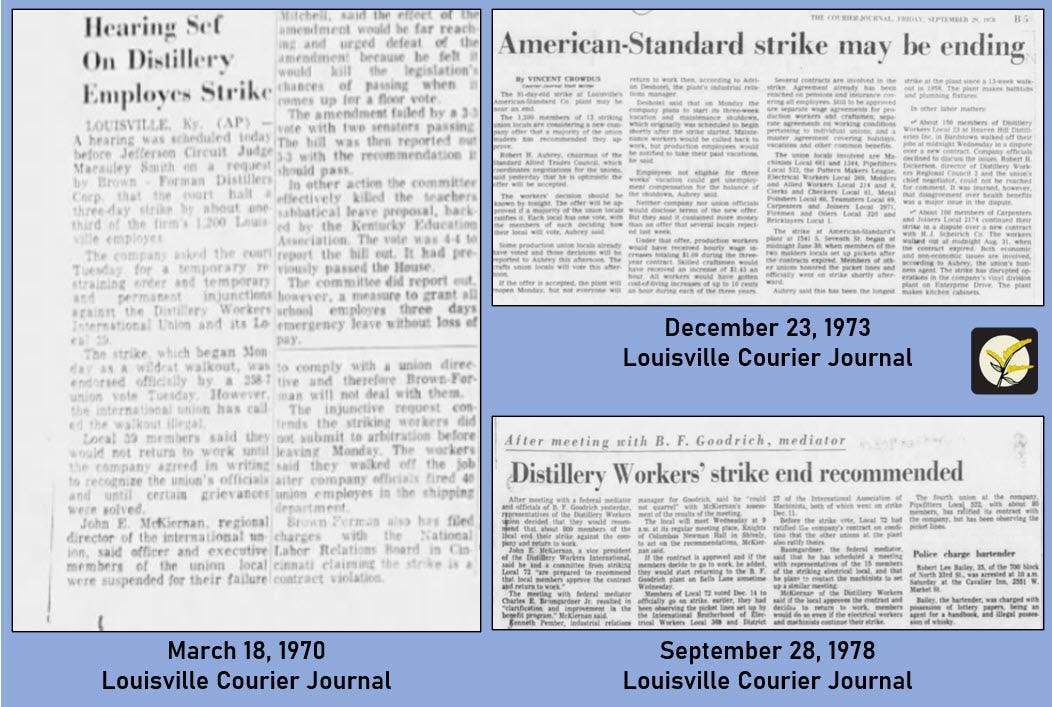

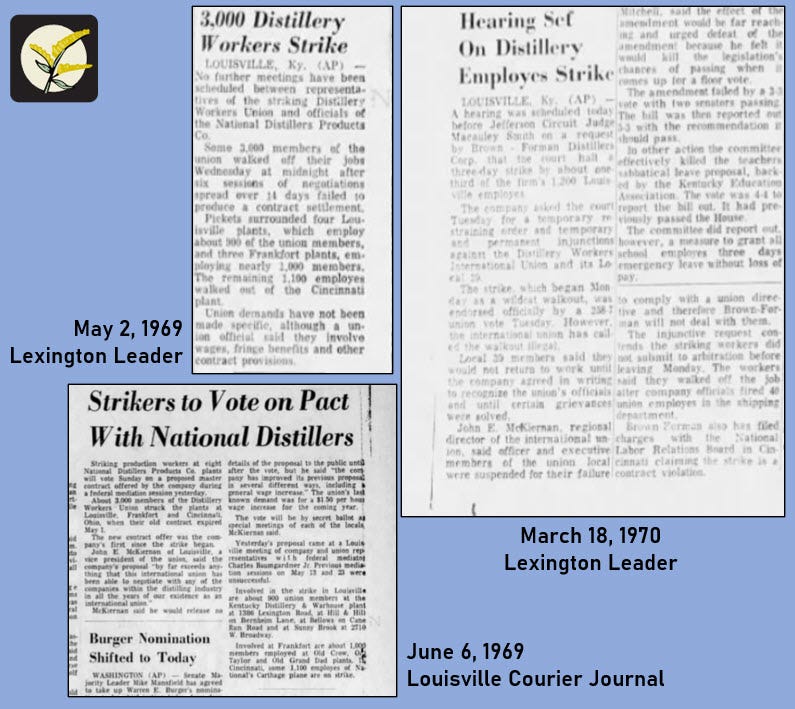

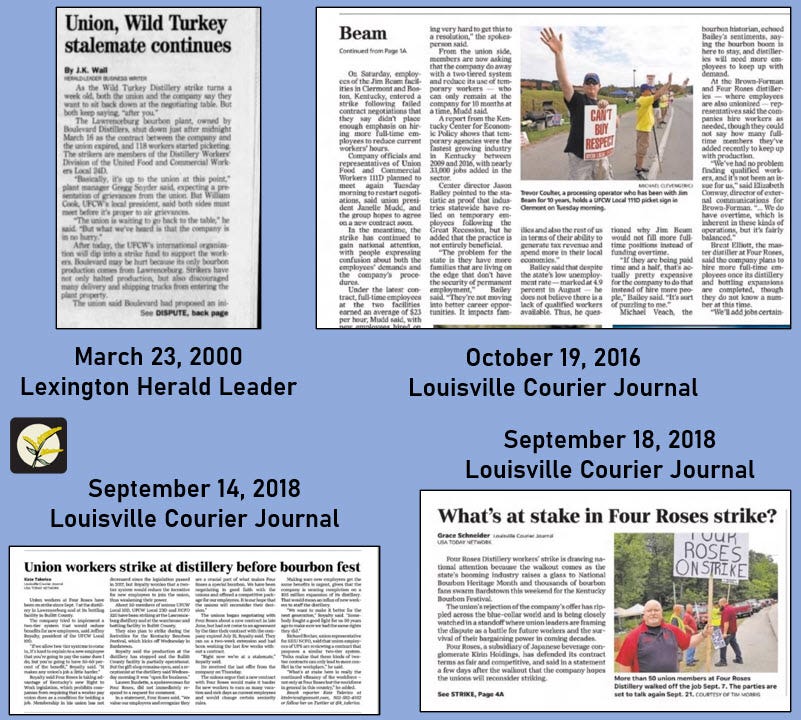

When you start digging in to old newspaper clippings in search of information about strikes within Kentucky’s bourbon industry, it becomes readily apparent that, over the past 100 years, these events have rarely been front page news. Tucked between obituaries and written in teeny-tiny font on page B11 next to an ad for headache powder, the struggles faced by the workers who create Kentucky’s signature spirit have long gone largely overlooked. Until now.

Read along as The Goldenrod’s new (!) food and drink labor reporter, Michelle Eigenheer, shines a light on almost 100 years of Kentucky bourbon industry labor strikes, all set in the context of this year’s Heaven Hill walkout. Can bourbon’s corporate powers-that-be learn from the past and ensure the industry’s employees have fair working conditions before other distillery contracts come up for review in the coming years—or will it be history repeating?

Images of workers in fluorescent orange vests holding signs in front of steepled Kentucky rickhouses gained attention across the country this fall as over 400 unionized workers at Bardstown’s Heaven Hill Distillery went on strike. For well over a month, members of United Food and Commercial Workers Local 23D joined a growing number of notable striking food producers, including Nabisco, as the distillery that skillfully creates some of bourbon’s most recognizable labels—Elijah Craig, Evan Williams, Henry McKenna and Larceny, to name a few—took to the picket lines over major contract disputes.

But bourbon workers striking in Kentucky is nothing new, and as the cavern between product demand and fair working conditions continues to grow amidst bourbon’s national resurgence, there’s plenty of history to trace.

Kentucky’s bourbon industry, which accounts for 95 percent of the global inventory, saw a sharp rise in popularity just over a decade ago, when the pendulum of trendiness and taste swung back toward the commonwealth’s signature spirit. Global sales grew 40 percent between 2008 and 2013, a dramatic pivot for an industry that had long been in decline, and by the end of this five-year window, bourbon exports from the state had reached $1 billion. Today, the Kentucky Distillers’ Association (KDA) reports that the Kentucky-born industry has reached a value of $8.6 billion, with production growing more than 360 percent since 2000.

A Kentucky distillery strike timeline—beginning in 1903—compiled by The Goldenrod. (View archival newspaper articles in full here.)

This industry success quickly brought curious outsiders to the rolling hills of the bluegrass, bolstering a tourism industry that has become one of Kentucky’s crown jewels. KDA reports that almost 2 million people now visit distilleries and other sites along the Kentucky Bourbon Trail each year, turning what were once mostly private, business-facing production operations into hospitality campuses, incorporating full-service bars, restaurants, hotels and other elaborate accommodations.

This includes Heaven Hill which, in 2017, pledged $25 million to expand its Bernheim Distillery in Louisville, then in 2018, promised a $125 million tourism-focused improvement effort—$19 million of which went toward an expansion of its visitor center. That same center celebrated its grand opening just three months before this year’s worker strike began.

A Kentucky distillery strike timeline—beginning in 1903—compiled by The Goldenrod. (View archival newspaper articles in full here.)

One week into the Heaven Hill worker’s 42-day strike this fall, the 30th annual Kentucky Bourbon Festival kicked off in Bardstown. The longstanding event—which typically adds approximately 50,000 weekend visitors to the town’s population of 13,000—for the first time limited the historically free, family-friendly festivities to only 7,000 people, ages 21-and-over, who where willing to pay $10/ticket for an “elevated” experience. And while other years would have brought thousands of tourists along the winding roads to nearby distilleries like Heaven Hill, this year, workers were striking miles away from where festivalgoers partied on.

Eventually, some of the striking workers made their way to the site of the festival event, bringing face-to-face the struggle of distillery laborers against a business that continues to boom on their backs. The situation put a fine point on one of the bourbon industry’s biggest problems: glossing over long-standing worker issues by attempting to glamorize their public-facing presentation and all but ignoring the behind-the-scenes reality necessary to keep up with ever-increasing demand.

And despite the expertly-crafted media campaigns spun by bourbon brands, what this explosively rapid growth has meant for workers tells a different story.

A Kentucky distillery strike timeline—beginning in 1903—compiled by The Goldenrod. (View archival newspaper articles in full here.)

Heaven Hill self-identifies as the fourth-largest spirits supplier in the world, but the distillery has had more labor strikes, or approvals for strike, than perhaps any other Kentucky distillery in recent memory: at least four since 1978. With the most recent vote to strike, 96.1 percent of union members were in favor, the highest it’s ever been in the local, according to Matt Aubrey, president of UFCW Local 23D, which represents workers at Heaven Hill, Four Roses, Barton 1792 and INOAC Packaging Group. Aubrey says this was a long time coming.

“20 years I’ve been in the unions, and I’ve never seen a 96.1 percent strike vote,” says Aubrey. “Heaven Hill workers are the lowest paid wage workers in our entire division. They get paid lower than anyone else out of the whole local. Not even just the local, but probably the state of Kentucky. When it comes to distilleries, they’re probably one of the lowest paid.”

A Kentucky distillery strike timeline—beginning in 1903—compiled by The Goldenrod. (View archival newspaper articles in full here.)

Aubrey, who was voted in as union president less than four months before contract negotiations with Heaven Hill began in September, says that he thinks workers felt forced to accept prior contracts despite being unhappy with them. In fact, they attempted to strike in 2016, around the same time as the first of the company’s two multimillion dollar expansion announcements.

Heaven Hill workers had voted an approval to strike, but reached a contract agreement before an actual walkout ensued. The company offered employees $7,250 in bonuses and a wage increase of $1.01/hour over the next three years to a room filled with lukewarm acceptance. Union officials cited upcoming expansion plans as a factor in the workers’ displeasure with the contract offer. “We bent over backwards to do everything for them, and they don’t want to give us anything,” bottling plant employee Troy Hardin told The Kentucky Standard at the time.

This year’s strike resulted in wage increases of up to $3.09/hour over the life of the 5-year contract. The new contract also protects workers from forced overtime and mandatory weekends, as well as reduces the number of temporary workers the company can bring in. Until now, with the industry’s dramatic increase in global demand, workers have had less control over how much time they have away from the production line.

“I think it’s been brewing up for some time now, and these workers just had enough,” Aubrey said. “They felt mistreated and they want to show how strong they are.”

And he predicts more changes to come.

A Kentucky distillery strike timeline—beginning in 1903—compiled by The Goldenrod. (View archival newspaper articles in full here.)

It’s an open secret that the bourbon industry in Kentucky has a murky history when it comes to the relationship between bosses and workers. As distillers labored to rebuild in the years following Prohibition, unionizing workers often met in violent conflict with distillery owners over demands for pennies more in their hourly wages during a time when collective bargaining power was essentially nonexistent. Their efforts? A footnote in the news of the day, as we’ve collected into a timeline spanning almost 100 years.

A short update in the December 15, 1903 edition of the Owensboro Messenger Inquirer contained a few, brief lines describing a Glenmore distillery’s strike in which workers asked for a daily wage of $1.25 instead of $1 and “would be replaced without delay.”

In the Frankfort Roundabout a few months later, tucked between an obituary and news that a local judge had just purchased a second lot on which to build a grand home, two sentences about a group of 25 girls who threatened to strike at a distillery in Tyrone and were “promptly discharged” snuck its way into the paper. The distillery, located just east of Lawrenceburg, was eventually acquired by Wild Turkey.

A Kentucky distillery strike timeline—beginning in 1903—compiled by The Goldenrod. (View archival newspaper articles in full here.)

Other walkouts, including those at National Distillers—then the largest operation in the country, later selling their spirits division to Jim Beam—were coordinated blows to industry. For National Distillers in 1950, 1969 and 1978, thousands of Kentucky workers walked out, and at Seagram & Sons in 1945, 1,000 Louisville workers joined approximately 3,000 others in Baltimore, Indiana and Ohio as part of a wildcat strike.

Today, as the labor movement and bourbon industry both gain strength in Kentucky, it’s easy to see why the two interests are clashing once again. After all, there’s a sense of family tradition, Aubrey says, when it comes to working at Heaven Hill. “The vast majority of people that work there, when I speak to them say, ‘Oh, yeah, my grandparents retired from here. My parents retired from here. My son now works here, or my daughter. And at the end of the day, with these types of jobs, it’s a skilled trade. But when it comes between the union and the corporation, especially with Heaven Hill—it’s not a family.”

“I think what happened at Heaven Hill is definitely a domino effect,” he says, laying out a timeline of upcoming contract expirations at other distilleries: Four Roses in 2023; Barton in 2024; and Jim Beam in a matter of months. “You’ve got three powerhouses right there that are back-to-back-to-back.”

“I think that the workers standing up and showing corporations that they deserve better might save these other distilleries,” Aubrey says in hope that Heaven Hill’s 42-day strike might give company leaders pause. “This might make them realize, ‘Maybe we need to step back and look at these workers that make us this profit. And maybe we need to start taking better care of them.’”

“Now in regard to not having strikes: The reason is they pay a living wage. What man wouldn’t work for an industry which pays him enough to keep a family together?” — brewery worker Don Matheny, October 20, 1946, Louisville Courier-Journal

Want to hear more about labor issues in the bourbon industry? Make sure to check out our interview—including audio!—with Four Roses distiller and former union president Jeff Royalty.

Also, if you have any archival materials from strikes we’ve missed, feel free to send it along. We’re looking to build out the most thorough, complete timeline possible.