Decayed and Delayed: Capturing the Vulnerable Infrastructure of Eastern Kentucky

When new infrastructure projects are announced for eastern Kentucky, even the thought that some improvements might be coming to do more than hold the region together with the construction equivalent of Band-aids, hot glue and pure luck is met with great fanfare. Promises to repair a road that’s sliding off the mountainside? A new dam to pacify local business owners? Guarantees of rehabilitated bridges? Cue the confetti cannon!

What’s not talked about enough, though, is the follow through—or lack thereof—on these infrastructure promises. New infrastructure, if it ever materializes, often arrives begging the question, Who is this actually helping? All the while, old infrastructure that once served the region’s most rural reaches is continuously left to the elements: reclaimed by kudzu or rusting into oblivion as town populations dwindle and the push for new-and-shiny heaves forward.

Will Major—a Baxter, Kentucky photographer and regular contributor to The Goldenrod—captures how years of neglect, benign or not, have left many once-robust infrastructure projects in and around Harlan County dilapidated, delayed or dried up, further positing: How do major investments of government dollars actually serve local communities long-term?

Baxter Bridge, Harlan, Kentucky

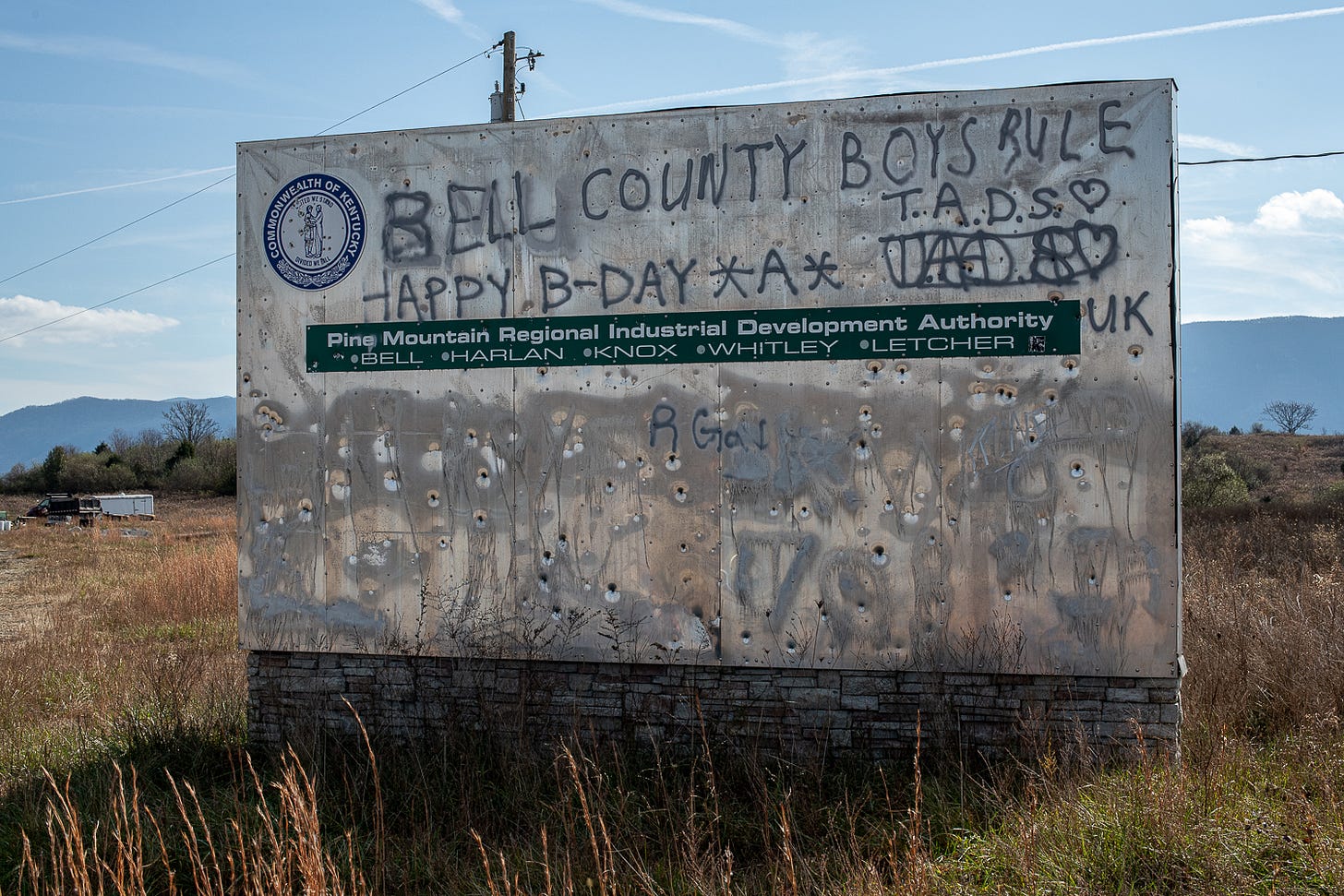

Boone’s Ridge, Bell County, Kentucky

It’s difficult to overstate just how much Abandoned Mine Lands Economic Revitalization (AMLER) money the Boone’s Ridge project received vis-à-vis other projects—and how little has been accomplished in delivering on promised development and jobs.

$12.5 million in AMLER funds were awarded to a nonprofit development group, the Appalachian Wildlife Foundation, in 2016 to build an 80,000-square-foot wildlife center on abandoned mine lands in Bell County. This disbursement—the largest of all AMLER grants in Kentucky—was followed up with a couple of additional federal monetary injections a few years later: $23 million in loan guarantees from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and $3.1 million from the Appalachian Regional Commission for constructing infrastructure. Since that time, the project has ballooned from a (completely feasible) wildlife center into a proposed $56 million, 12,000 acre outdoors destination. (No doubt for “adventure tourism.”)

Curiously, the nonprofit’s executive director says they still need an $10 million to complete the project by 2023.

Hal Rogers’ Bridge to Nowhere, Boone’s Ridge, Bell County, Kentucky

“By now, the Appalachian Wildlife Center, which has rebranded itself as Boone’s Ridge, was supposed to be pumping millions of dollars into Bell County. It was expected to have created more than 1,000 direct and indirect jobs in the region, as many as the county’s two largest employers combined,” R.G.Dunlop wrote for ProPublica in October 2020. “Instead, a countdown clock on the project’s website winds down to the most recent opening date: 593 days away.”

Despite an ever-growing budget and scope, the project now anticipates to bring only 250 direct jobs to Bell County—and the same countdown clock says that there are 376 days until opening.

Georgetown Bridge, Harlan, Kentucky

Georgetown was a historically Black community on the west bank of the Cumberland River in Harlan County that was destroyed by flooding in 1977. It’s also a key example of the often-ignored impacts of environmental racism in eastern Kentucky. The Georgetown Bridge (pictured above in its 2022 condition) was utilized daily by residents to make the 10-minute walk into downtown Harlan, though the bridge is particularly low slung and was threatened by flooding every time it rained more than a few inches.

Prior to the devastating natural disaster, Georgetown residents had been battling for years against Harlan city official’s racist plan to remove them from their homes through condemnation proceedings that would clear the Georgetown area to make way for, among other things, a new high school athletic field.

“‘If they don't want the plan as we laid it out, let them sit there,’” City Councilman Ernest Smith told The New York Times in December 1975. “‘Maybe nature will do something that we couldn't do,’ he continued, alluding to a possible flood.”

Less than two years later—due in large part to landfill operations along the banks of the Cumberland River exacerbating the rising waters near Georgetown—this once-thriving Black community was completely dismantled due to a flood.

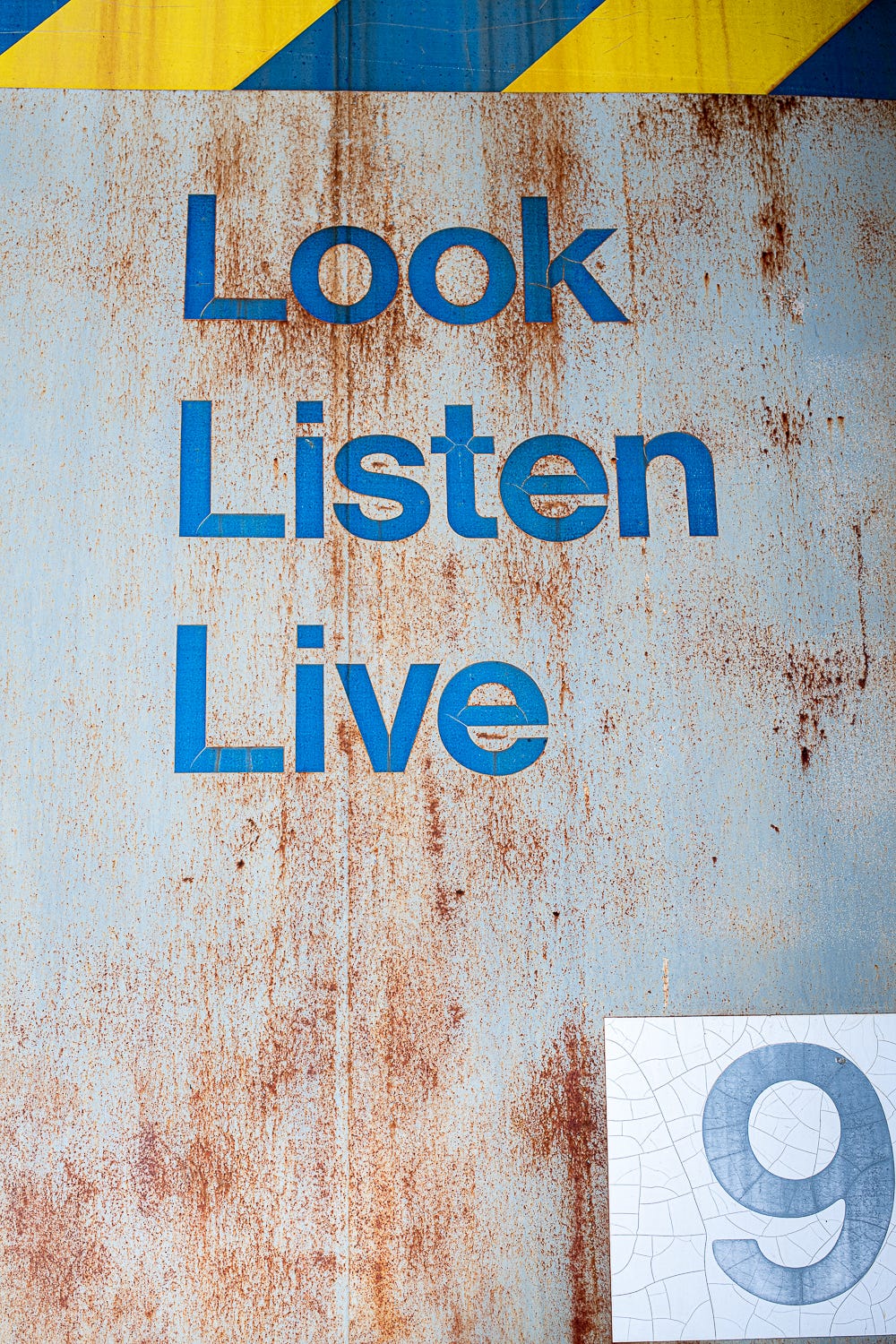

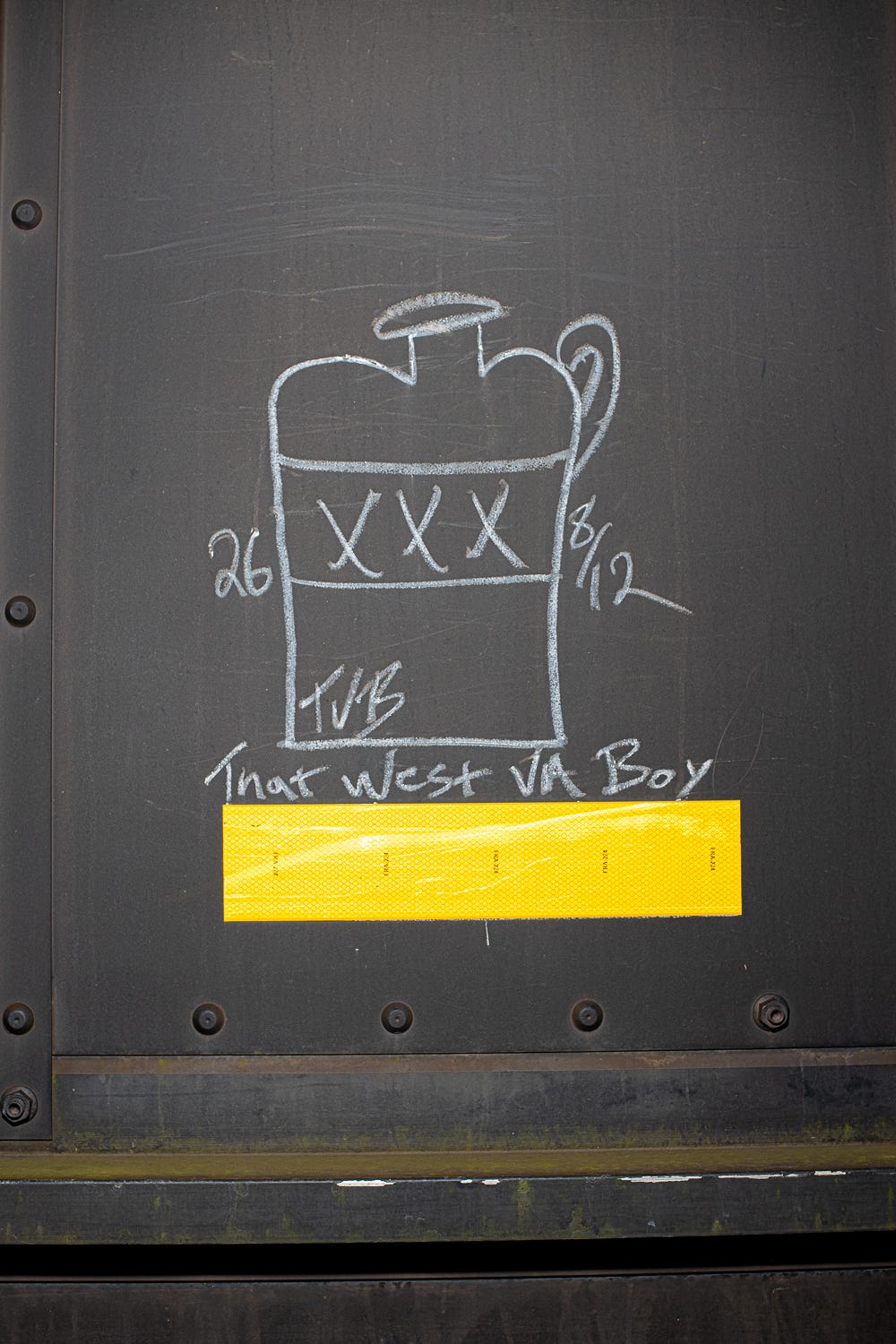

Loyall Train Yard, Loyall, Kentucky

The new “sign” reads: Loyall D.I.Y. / Est. 2015 / Loyall D.I.Y. Rules! 1. To skate, you must work! 2. Throw away trash 3. Be respectful to neighbors. (No loud cussing)

Loyall Train Yard, Loyall, Kentucky

“Growing up in the coalfields of Appalachia, Louisville & Nashville’s coal marshaling yard at Loyall, Ky., was legendary. Built in 1921 to serve the burgeoning coal mining of Harlan County and situated in the very heart of that country, Loyall Yard was the main hub of L&N’s Cumberland Valley Subdivision,” Eric Miller wrote for Railroads Illustrated in 2016.

“In February 1991…I made my first trip to Loyall, my best friend in tow. Bereft of a map, I had no idea how to get there beyond in just a general sense. After a morning of wrong turns and dead-ends, we finally found ourselves at the entrance to Loyall Yard. Viewing from a safe (not trespassing) distance, I could see that the sprawling yard was abuzz; mine runs were shuffling cars, loads and empties, coal and woodchips and logs. I saw a roundhouse, a turntable, and a track of active service cabooses. There was a compact engine terminal packed full of big SDs and C30-7s, as well as U23Bs and GP38-2s in Chessie, Family Lines, L&N and CSX colors. The legend, now realized, did not disappoint.”

The Loyall Train Yard is decidedly less bustling—and more disappointing—these days.

Loyall Train Yard, Loyall, Kentucky

Loyall Train Yard, Loyall, Kentucky

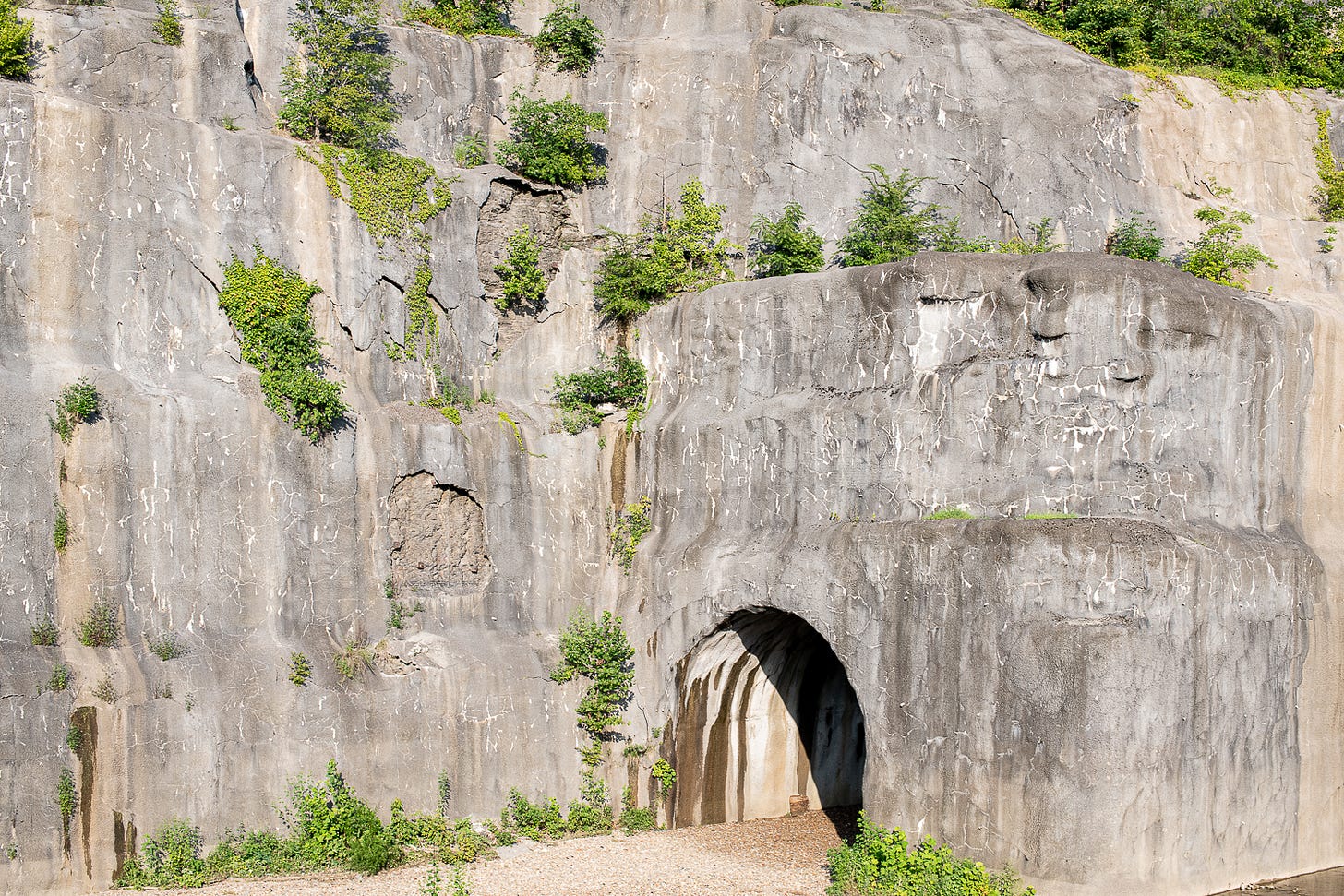

Clover Fork Diversion into the Harlan Tunnels, Harlan, Kentucky

In October 1999, Rep. Hal Rogers (who else?) dedicated the Harlan Flood Control Project: an effort to create “maximum levels of flood protection for the towns of Harlan, Baxter, Loyall and Rio Vista in Harlan County” by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) that spanned over the course of a decade and cost a whopping $181 million.

In stage one of the project, the Corps of Engineers constructed four 2,000-foot tunnels through Ivy Hill to divert flows from Clover Fork around Harlan’s central business district. “About 600 people watched and cheered when the Corps first diverted the water through the tunnels Sept. 21, 1992,” according to the USACE. (You can watch a video of the diversion construction here.)

Clover Fork rerouted into the Harlan Tunnels, Harlan, Kentucky

Today, the Clover Fork diversion tunnels are looking rockier, muddier and more scrubby-brush-and-vegetation-filled than, well, wet.

Clover Fork rerouted into the Harlan Tunnels, Harlan, Kentucky

All photos by Will Major.

We’ll be back Thursday to continue this series exploring how old infrastructure projects are faring in and around Harlan County, how climate change has shifted infrastructure needs in Appalachian Kentucky—and what can be learned before new project arrive.

Wonderful reporting! I work for Kentucky Heartwood, and we are working on creating awareness in Rowan County in the Daniel Boone National Forest regarding road improvement projects, stream restoration funds, and potentially millions of dollars of questionable government spending. If you have any bandwidth, we are looking for reporters who are interested in digging into this. Please contact Lauren - kentuckyheartwood@gmail.com if you're interested to learn more!