Bringing Free HIV and Hepatitis C Testing to Rural Kentucky, One Pop-Up Site at a Time

Kentucky Finding Cases is hitting the streets to address a public health crisis head on (and breaking down stigma along the way).

“Oh, wow, we've got a lot in common!” Eric Barker smiles, his eyes lighting up. “Just like you’re trying to address the news desert here, that's how we’re trying to fight the HIV epidemic—by fixing the testing desert in Eastern Kentucky. People weren’t getting tested, they weren’t getting PReP, and that's really where we sprouted from.”

Barker is a social worker, certified alcohol and drug counselor and peer support specialist in long-term recovery who works for Kentucky Finding Cases (KFC), a new program that provides free HIV and hepatitis C testing, linkage to care, and other resources for HIV and hepatitis C positive clients in four vulnerable regions across Kentucky. A pilot effort that’s part of both the Kentucky AIDS Drug Assistance program and income reinvestment through the University of Kentucky (with a grant that’s funded through at least 2023), Barker works in Region C—Boyd, Lawrence, Elliott, Carter and Greenup Counties—alongside Charlie Pack, Jessie Kennard and Allison Myers.

(Kentucky Finding Cases Region C, highlighted in blue, via Facebook)

Pack, the region’s director, worked for 18 years as a social worker and in long-term care before transitioning to Kentucky Finding Cases, while recent college graduate Myers got her start in a community mental health center focusing on alcohol, tobacco and drug prevention in youth.

For Kennard—who was employed by a regional rehab facility prior to her current role and calls herself a “freelance case manager”—the work is deeply personal. “I have a background in substance use, but as a spouse: my husband was a long-term heroin and meth addict. I’ve experienced the other end of just observing addiction. It helps me relate to people where they're at.”

Barker agrees. “A lot of this did stem from the opioid epidemic, and I have a history of use, so it allows for an easier transition to talk to people about hepatitis C, about HIV, about substance use and getting in treatment. But we don't push anything on anybody. It just allows me to talk to people on another level.”

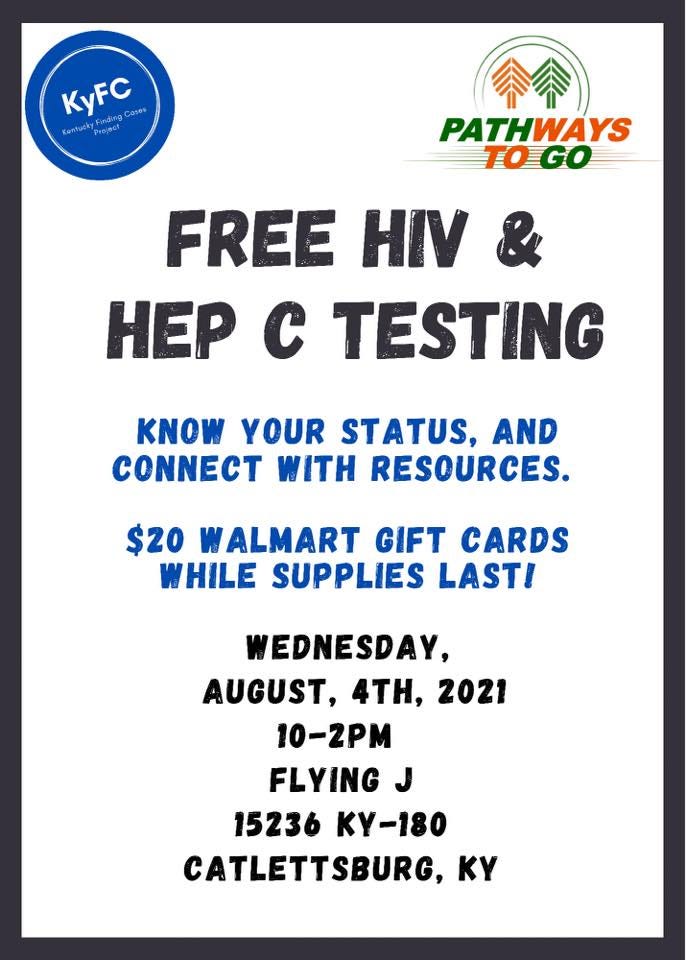

Kentucky Finding Cases is constantly out in the streets, advertising free testing sites across northeastern Kentucky’s rural reaches and mountainside neighborhoods, from Flying J gas stations and flea markets to Save-a-Lot parking lots and veteran halls. The program uses a rapid test for both HIV and hepatitis C, ensuring that the individuals being tested know their results within 10-15 minutes. “We just tell them right there, which is great because it’s not a blood draw that could take a long time,” Myers says. High-risk individuals are also able to test for free every three months, as antibodies usually takes about 90 days to show up on a rapid test.

“Sometimes people come back, even though it’s only been like a month. We also have harm reduction items such as condoms and lube. We give away snacks, all those type things,” says Pack. “And sometimes they'll just come, grab a few snacks, and just sit and chit chat with us.”

Below, the Kentucky Finding Cases team discusses how they’re breaking down barriers to HIV and hepatitis C testing across Eastern Kentucky, the opioid crisis’s impact on the region and the importance of pushing back against the stigma of addiction.

(Myer and Kennard at a flea market in Russell, Kentucky, June 2021, via Facebook)

Sarah Baird: How did Kentucky Finding Cases get off the ground?

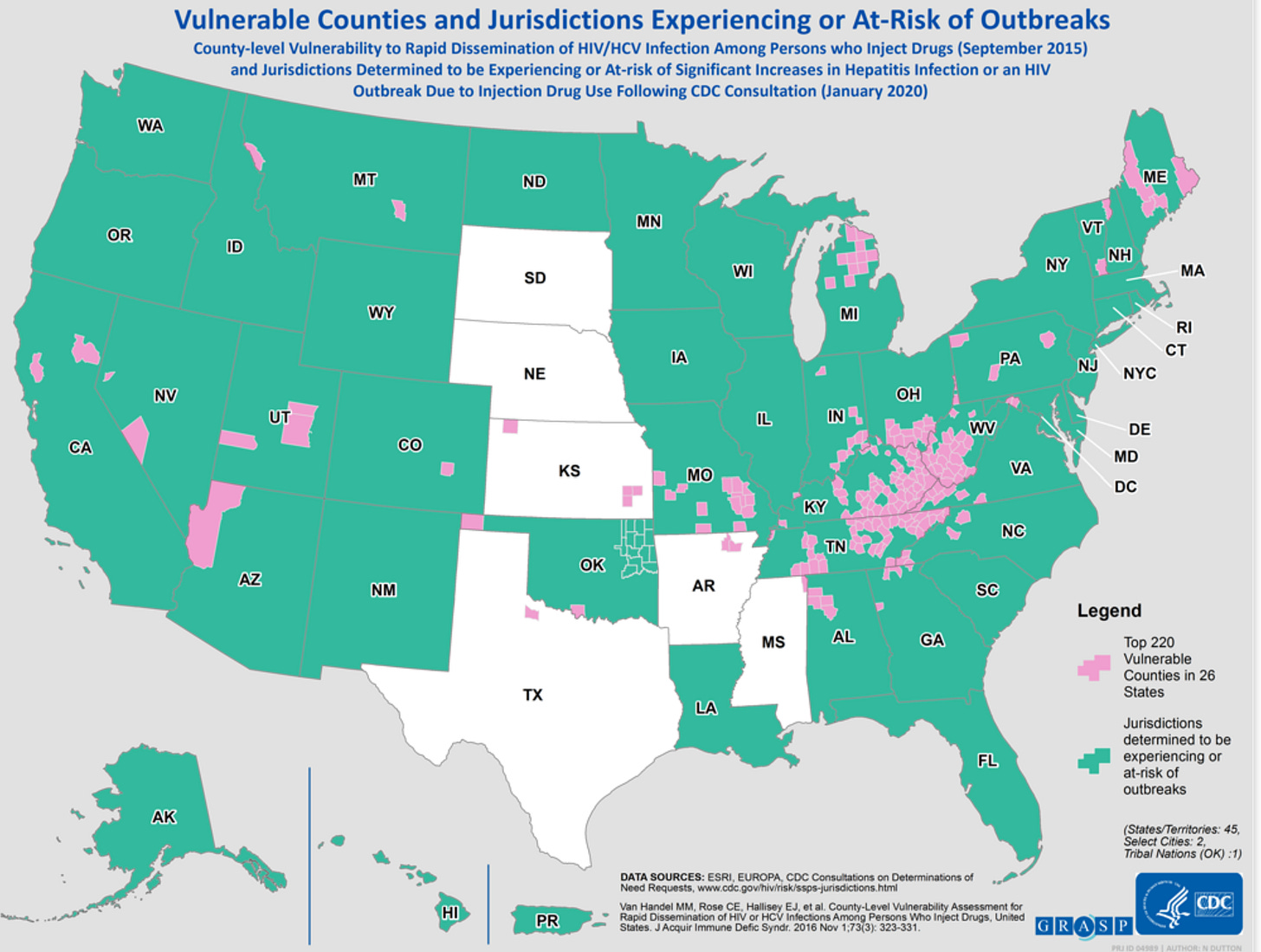

Charlie Pack: When the CDC did a study of the 220 most vulnerable counties in the United States for HIV and hepatitis C outbreaks, out of the 220 counties, 54 of them were right here in Kentucky. Almost half of our Kentucky counties qualified as currently experiencing—or being at risk for—a hepatitis C or HIV outbreak, with Wolfe County being number one in all of the United States. The counties in our area range [on the CDC’s risk list] from the 39th position to 180. Opioid addiction caused a perfect storm for HIV and Hepatitis C outbreaks in Eastern Kentucky.

Boyd County, if they redid the study, would probably be much higher, because we’re here in the tri-state area. With Huntington [West Virginia] having that huge HIV outbreak in the last few years, we expect to see that trickle over to Boyd County, because it's kind of like a little circle here.

(via the CDC)

Alison Myers: We’ve only been testing for a year-and-a-half, and within the last year, we have tested 1,385 people in our region. We don't just test and run. I think my favorite thing about our current program is when people come back to us. Especially when it’s people in the homeless community and they're like, “Hey, I got finally got my apartment," or “Hey, I'm really hungry,” or “I need some clothes. Can you help me?” They know us. They seek us out. They're so comfortable with us that they can talk about what they need.

SB: Y’all are in communities constantly testing and interacting with people. What is the current state of rural housing insecurity in Eastern Kentucky? Has COVID impacted things?

AM: We see a lot of homelessness in Ashland.

Eric Barker: People migrate toward Ashland because of resources like The Neighborhood. So, it's not just people from Ashland. It's people from throughout Kentucky. We've tested multiple people from Wolfe County, for instance. You'll find people will migrate to where there are resources.

Jessie Kennard: I personally feel like COVID hasn't really contributed to homelessness here. It's just the drug use. Some days, you get really discouraged because you're fighting so hard to help people, and it just seems like it's not going away or something new pops up.

CP: What we see in the homeless community is that because of the rules in HUD programs, you can't have any felony charges or be in active addiction to receive housing.

I think homelessness has grown due to word-of-mouth more than COVID because people are now getting on the bus and coming here knowing the services that Ashland offers. We tested some people from Oregon the other day. We've tested people from, shoot, I don't know, Detroit. Oklahoma. Folks from all over. And most of them say that some family member came here and sent them a message, so they just got on the bus and came as well. It's one of the friendliest homeless places you could come, I would say, not just in Kentucky, but the United States, because we're a one-stop shop at this point with CAReS [Community Assistance and Referral Services] and The Neighborhood.

SB: How do you determine the best places for testing sites in the more rural parts of your service area?

CP: We know the neighborhoods and places were our target population hangs out, but we also drive around and sometimes we'll be like, “Oh, we need to set up here!” It really is a team effort, especially in the more rural places like Elliott County. We’re always thinking of ideas about where we need to be in our community and spots we might be missing.

EB: Other than hit the streets, we've been under bridges and down by the rivers. We'll pick days just to go explore where various populations are gathering and talk to people, especially in rural Eastern Kentucky. I mean, in Carter County, there are four or five smaller cities. So, you're trying to find those community centers where you can reach out to meet people where they're at. It's just crazy where we’ve been, but I think every time we've gotten people to test, so it’s been pretty cool.

AM: We work with food pantries a lot, so we try to find when they're open, and then we also have a big partnership with Pathways Community Mental Health Center. They have a mobile RV—it’s really nice. They try to help people get into mental health and addiction services, so we partner with them. We’re usually on that RV with them most of the time.

SB: Are people hesitant to get tested? What are the conversations like encouraging people to get tested?

AM: Well, we have $20 Walmart gift cards [for people who get tested], so that’s a big one! If we didn't have those, I don't know how it would be. A lot of times, people aren't very educated about HIV and hepatitis C. We’ve had a few HIV positives, but we’ve seen a lot of hepatitis C. That's the big thing around this area, and a lot of people are just uneducated about how hepatitis C is curable now. You can get treated. A lot of people don't know that. And although it's not curable, HIV is treatable now with medication so you can live a long, healthy life. It's come a long way.

A lot of people are afraid, I think, but really, they're just uneducated, so we try to educate about everything. If people are high risk for HIV, we provide them with resources like access to PrEP, which is a pre-exposure prophylaxis. We can get them on that medication. We also refer our positives to treatment if they want it. We kind of try to do it all.

CP: We're testing hepatitis C [positives] at just a little over a 20 percent rate right now on the RV. It probably would be higher if the people who already knew their status got tested, so I would say we’re closer to 25 or 30 percent [positive]. Some are shocked when they find out their status; some probably already know; and some just feel like they're probably going to have it. With the ones who are shocked, it’s a little more difficult to have that conversation, but with it being curable now, they take it a lot better after being educated.

An HIV positive, well, delivering that message never becomes easier. The counseling session is pretty intense. We set up care. We have to call the HIV line. It's usually about an hour conversation, and we lock the back of the bus up. If they want into treatment, we'll set their appointment up right there. If people know they're higher risk, you see them sweating it out a lot before the test. But we try to educate them enough while we're doing the test that, if we do have to give that result, they know it's not as bad as it used to be. It’s not a death sentence.

(Partnering with Kentucky Finding Cases Region F in Phelps, via Facebook)

EB: We also do a lot of breaking down of the stigma around hepatitis C because how they treat it has changed. The medication is the same, but the technique's not. Before, you had to be six months sober and have high fibrosis levels. One of the things I’d say that’s really led to the hepatitis C epidemic here is a refusal to treat high risk people in the past. So many people believe it's still these old standards to get treatment.

Until we came along, there weren’t easy connections. But we have connections with healthcare providers who will get the medication to our clients pretty instantly without judging and, again, meet them when they're at. It was a lot of backtracking to overcome those stigmas that people have received from former healthcare providers.

I also share my story. I've had hepatitis C. I've been treated for it, so it kind of removes some of that stigma of identifying with it. I have no qualms identifying with it these days, but I remember the fight I had in 2012 to get treatment. It took me six years. I was educated and knew where to go and still couldn't get it. So, it’s just daunting for our clients when they still think that’s the way it is when right now you can just go get a blood draw and get the medication with your insurance and eliminate it. We’re trying to make what happened in the past so much easier in the present.

SB: Do you think the community realizes that there’s this huge public health crisis happening in the region?

AM: I would say most people are still in the dark about HIV and hepatitis C.

JK: I say denial, not in the dark. It's still very stigmatized. We have people who don't even want to associate with our program because of HIV being a disease for certain people this side or the other. But there are a couple of churches in our community that have really opened their doors and let us come set up there, so I think what we’re doing is definitely changing some minds in our area. I'm very proud to say that we are reducing stigma on a daily basis.

EB: People are aware. Some people just choose to deny it, because you cannot drop into any city in Kentucky, I don't care where it’s at, and not realize that there’s a substance abuse problem going on with underlying medical and mental health issues. It’s just, do you choose to help, or do you choose to ignore? Unfortunately, a lot of people do ignore it. We’re making changes and moving stigma, but it’s still going to take a while.

Charlie: We’re in the streets a lot. A lot of the time these people just want someone to spend five minutes and talk with them. They’re human. We all have addictions. It might be nicotine, it might be caffeine, but here in America, we want to place levels on addiction. I know opioid addiction is illegal, but to these people their addiction is just the same as our nicotine or caffeine, and it’s hard to break once you get in that cycle.

When we go into Elliott County and more rural areas, a lot of people don't even know that there's help out there. It’s a community effort, and hopefully people will see that we're making a difference and they'll get on board and help make a difference with us.

Today is World AIDS Day, so why not consider giving a (small, large, whatever you can!) donation to AVOL, a group that’s been collaborating with communities to end HIV across Kentucky for over 30 years?

Another way to make a difference this winter is by getting involved with Eastern Kentucky Mutual Aid!

We’ll be back Friday bringing you a story filled with visions of currywurst and fine feathered friends. Know a pal who loves a good German snack? Consider buying them a gift subscription: